Foreword

Welcome to the Avast Q4’21 Threat Report! Just like the rest of last year, Q4 was packed with many surprises and plot twists in the threat landscape. Let me highlight some of them.

We all learned how much impact a small library for logging can have. Indeed, I’m referring to the Log4j Java library, where a vulnerability was discovered and immediately exploited. The rate at which malware operators exploited the vulnerability was stunning. We observed coinminers, RATs, bots, ransomware, and of course APTs abusing the vulnerability faster than a software vendor could say “Am I also using this Log4j library somewhere below?”. In a nutshell: Christmas came early for malware authors.

Original credits: XKCD

Furthermore, in my Q3’21 foreword, I mentioned the take-down of botnet kingpin, Emotet. We were curious which bot would replace it… whether it would be Trickbot, IcedID, or one of the newer ones. But the remaining Emotet authors had a different opinion, and pretty much said “The king is dead, long live the king!”, they rewrote several Emotet parts, revived their machinery, and took the botnet market back with the latest Emotet reincarnation.

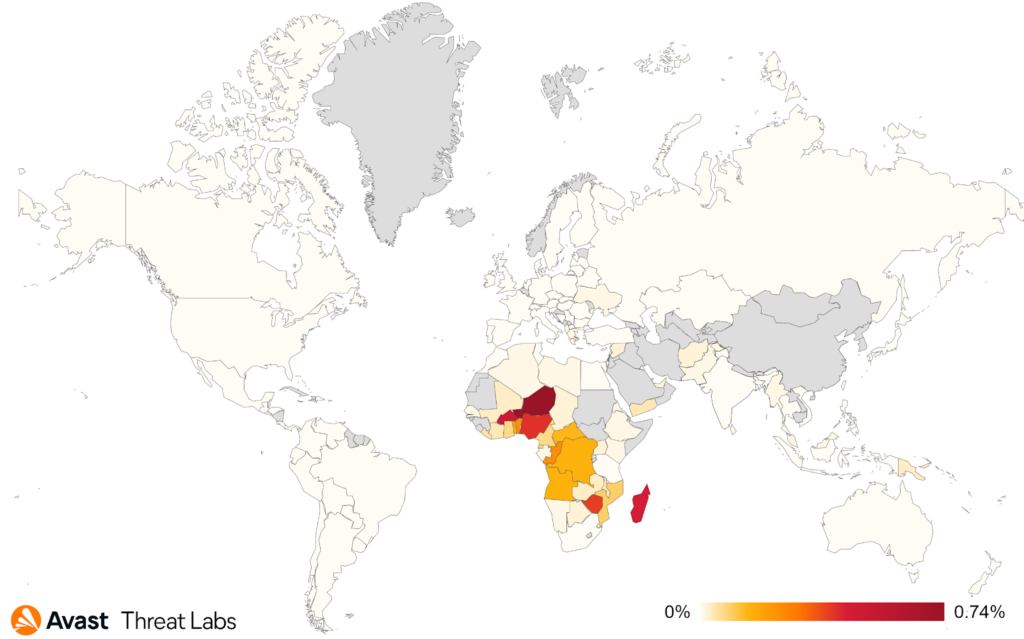

Out of the other Q4’21 trends, I would like to highlight an interesting symbiosis of a particular adware strain that is protected by the Cerbu rootkit, which was very active in Africa and Asia. Furthermore, coinminers increased by 40% worldwide by infecting webpages and pirated software. In this report, we also provide a sneak peek into our recent research of banking trojans in Latin America and also dive into the latest in the mobile threat landscape.

Last but not least, Q4’21 was also special in terms of ransomware. However, unlike in previous quarters when you could only read about massive increases in attacks, ransom payments, or high-profile victims, Q4 brought us a long-awaited drop of ransomware activity by 28%! Why? Please, continue reading.

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Methodology

This report is structured as two main sections – Desktop, informing about our intel from Windows, Linux, and MacOS, and Mobile, where we inform about Android and iOS threats.

Furthermore, we use the term risk ratio in this report for informing about the severity of particular threats, which is calculated as a monthly average of “Number of attacked users / Number of active users in a given country”. Unless stated otherwise, the risk is available just for countries with more than 10,000 active users per month.

Desktop

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)

Advanced Persistent Threats are typically created by Nation State sponsored groups which, unlike cybercriminals, are not solely driven by financial gain. These groups pursue nation states’ espionage agenda, which means that specific types of information, be it of geopolitical importance, intellectual property, or even information that could be used as a base for further espionage, are what they are after.

In December, we described a backdoor we found in a lesser known U.S. federal government commission. The attackers were able to run code on an infected machine with System privileges and used the WinDivert driver to read, filter and edit all network communication of the infected machine. After several unsuccessful attempts to contact the targeted commission over multiple channels, we decided to publish our findings in December to alert other potential victims of this threat. We were later able to engage with the proper authorities who are in possession of our full research and took action to remediate the threat.

Early November last year, we noticed the LuckyMouse APT group targeting two countries: Taiwan and the Philippines. LuckyMouse used a DLL sideload technique to drop known backdoors. We spotted a combination of the HyperBro backdoor with the Korplug backdoor being used. The dropped files were signed with a valid certificate of Cheetah Mobile Inc.

The top countries where we saw high APT activity were: Myanmar, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Ukraine. An actor known as Mustang Panda is still active in Vietnam. We also tracked a new campaign in Indonesia that appears to have been initiated in Q4’21.

The Gamaredon activity we observed in Q3’21 in Ukraine dropped significantly about a week before the Ukrainian Security Service publicly revealed information regarding the identities of the Gamaredon group members. Nevertheless, we still saw an increase in APT activity in the country.

Luigino Camastra, Malware Researcher

Igor Morgenstern, Malware Researcher

Daniel Beneš, Malware Researcher

Adware

Adware, as the name suggests, is software that displays ads, often in a disturbing way, without the victim realizing what is causing the ads to be displayed. We primarily monitor adware that is potentially dangerous and is capable of adding a backdoor to victims’ machines. Adware is typically camouflaged as legitimate software, but with an easter egg.

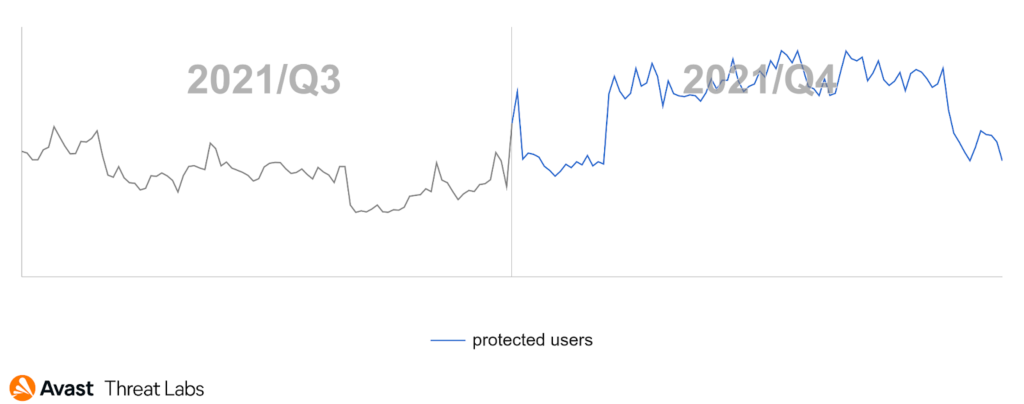

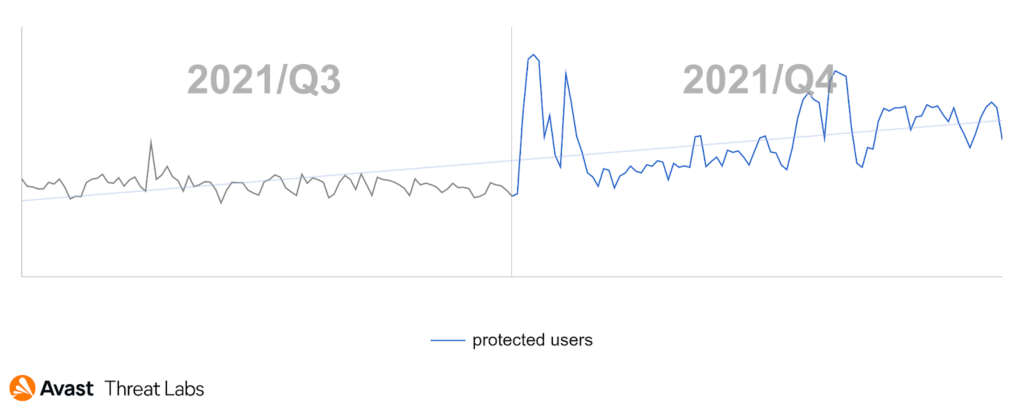

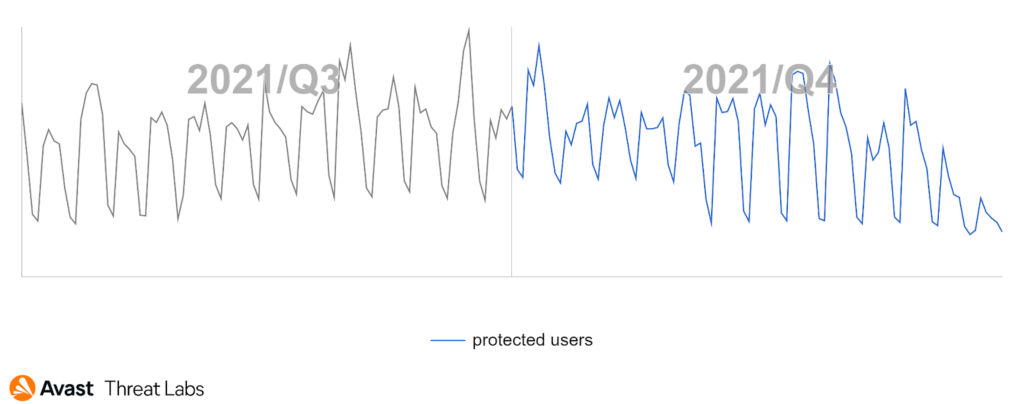

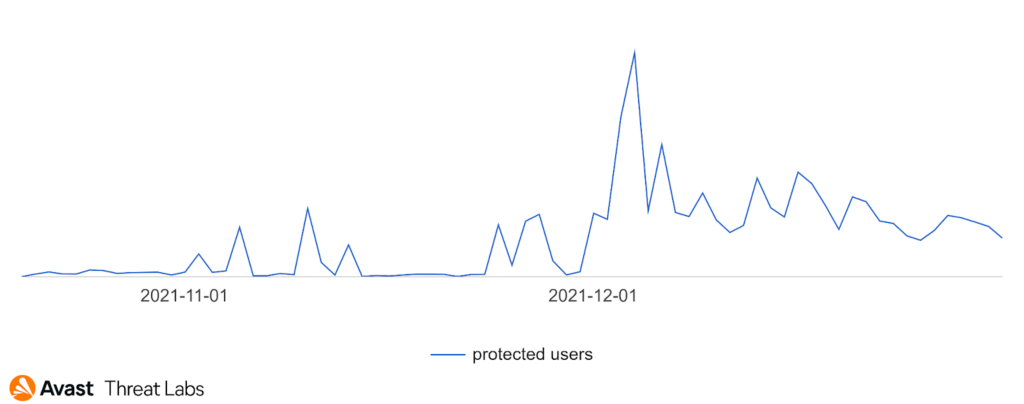

Desktop adware has become more aggressive in Q4’21, illustrated in the graph below. In comparison to Q3’21, we saw a significant rise in adware in Q4’21 and a serious peak at the beginning of Q4’21. Moreover, the incidence trend of adware in Q4’21 is very similar to the rootkit trend, which will be described later. We believe these trends are related to the Cerbu rootkit that can hijack requested URLs and then serve adware.

The risk ratio of adware has increased by about 70% worldwide in contrast to Q3’21. The most affected regions are Africa and Asia.

In terms of regions where we protected the most users from adware, users in Russia, the U.S., and Brazil were targeted the most in Q4’21.

Martin Chlumecký, Malware Researcher

Bots

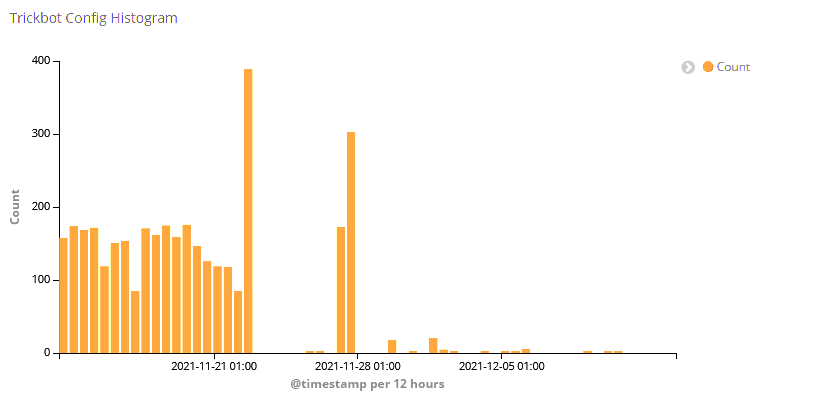

The last quarter of 2021 was everything but uneventful in the world of botnets. Celebrations of Emotet’s takedown were still ongoing when we started to see Trickbot being used to resurrect the Emotet botnet. It looks like “Ivan” is still not willing to retire and is back in business. As if that wasn’t enough, we witnessed a change in Trickbot’s behavior. As can be seen in the chart below, by the end of November, attempts at retrieving the configuration file largely failed. By the middle of December, this affected all the C&Cs we have identified. While we continue to observe traffic flowing to a C&C on the respective ports, it does not correspond to the former protocol.

Just when we thought we were done with surprises, December brought the Log4shell vulnerability, which was almost immediately exploited by various botnets. It ought to be no surprise that one of them was Mirai, again. Moreover, we saw endpoints being hammered with bots trying to exploit the vulnerability. While most of the attempts lead to DNS logging services, we also noticed several attempts that tried to load potentially malicious code. We observed one interesting thing about the Log4shell vulnerability: While a public endpoint might not be vulnerable to Log4shell, it could still be exploited if logs are sent from the endpoint to another logging server.

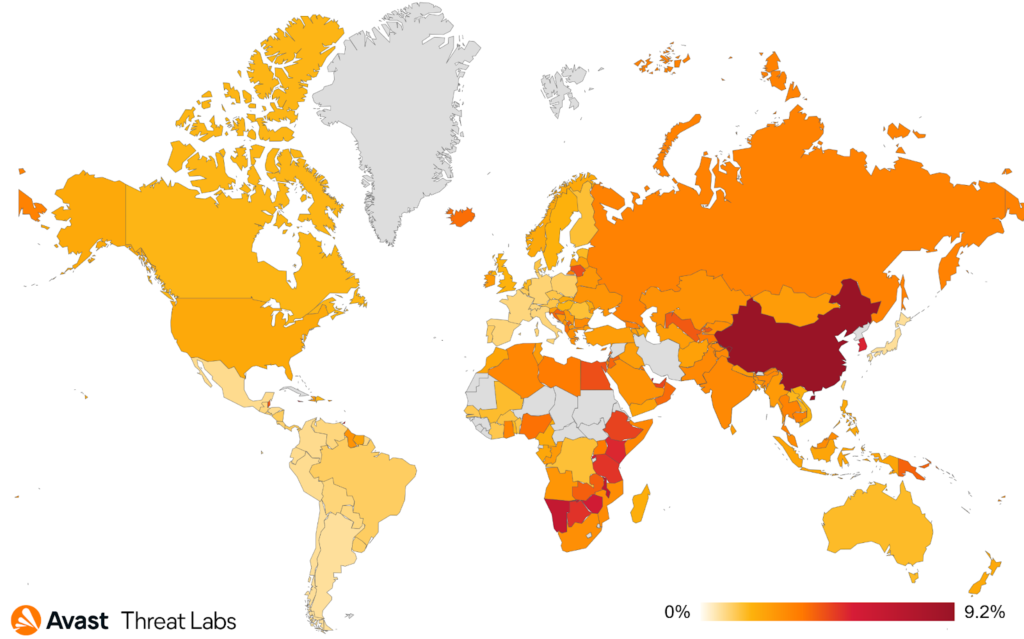

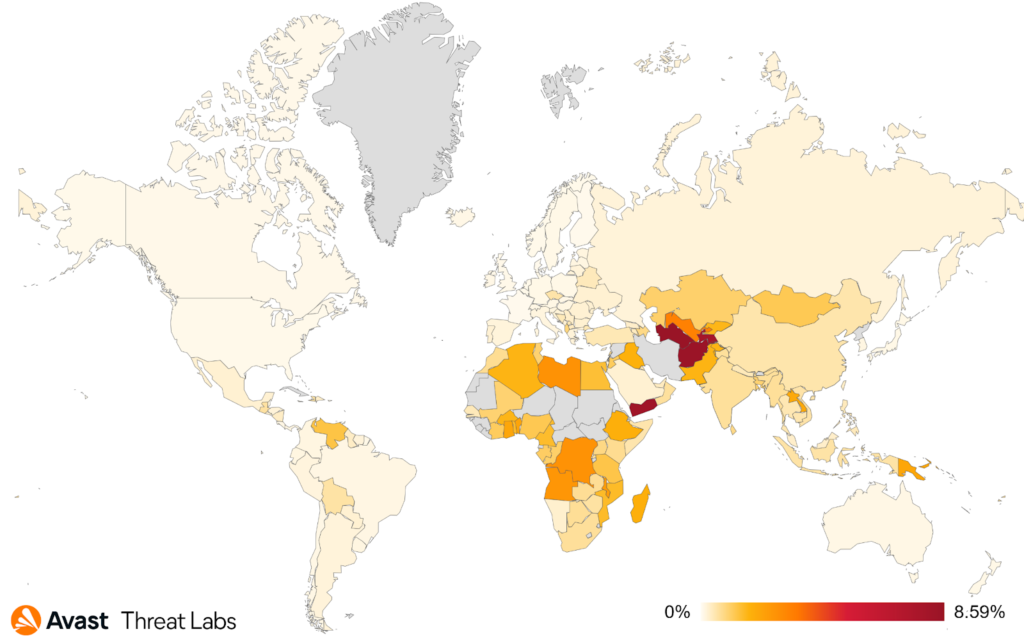

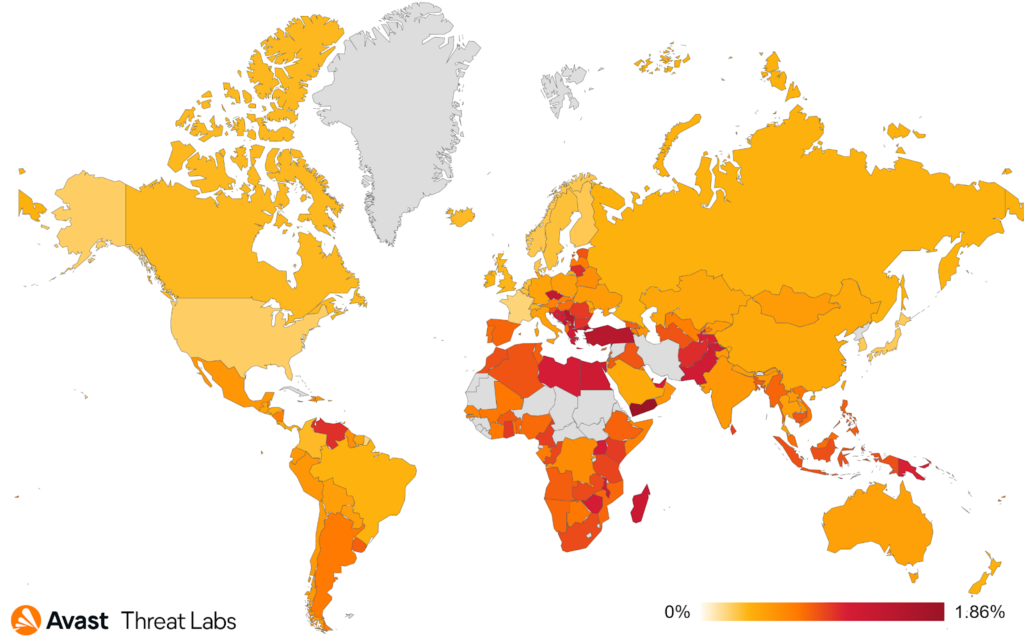

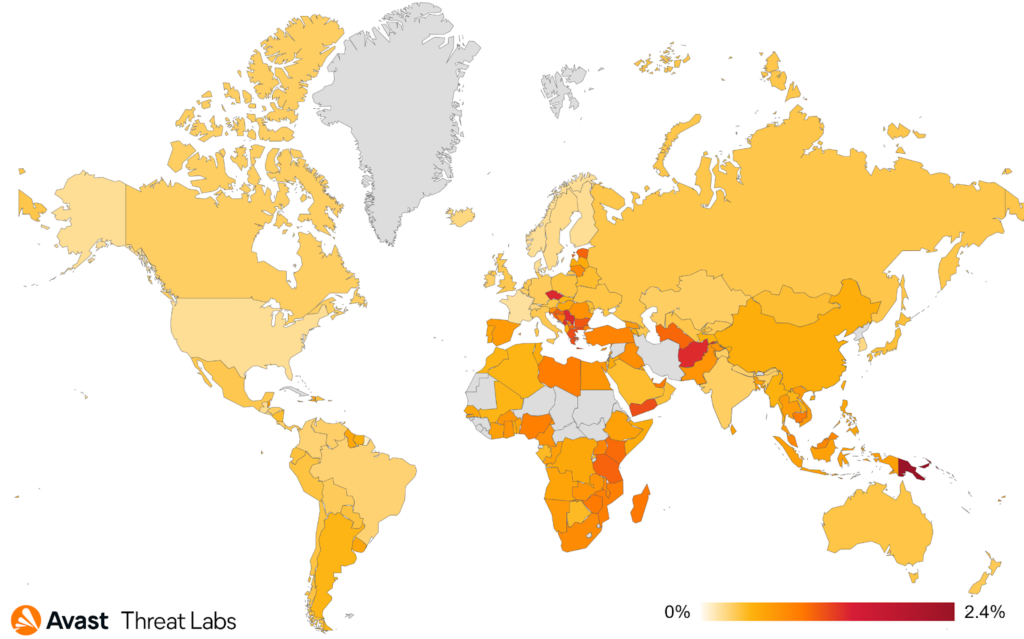

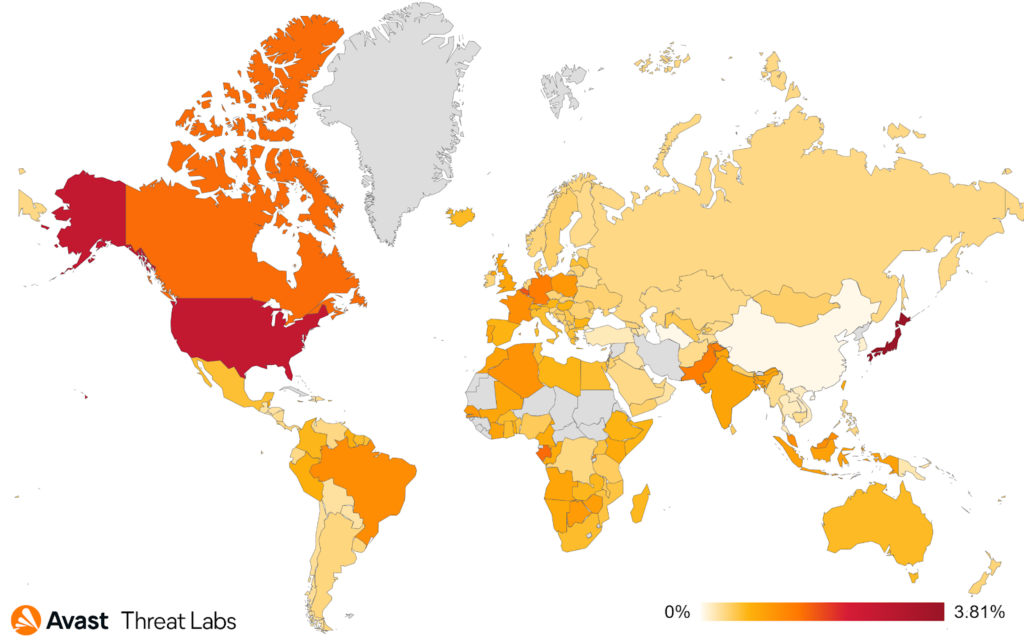

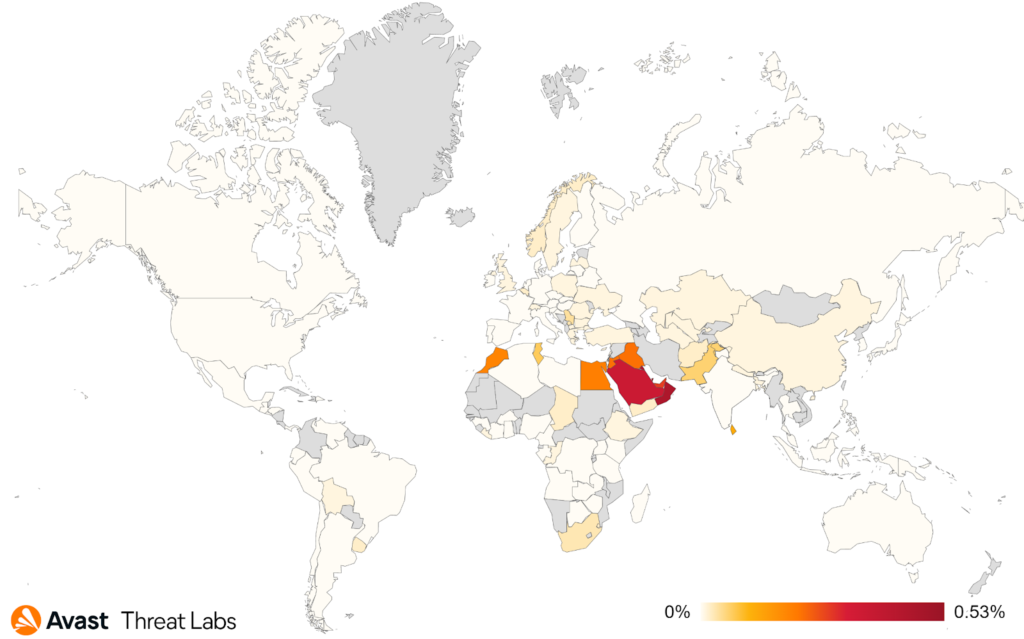

Below is a heatmap showing the distribution of botnets that we observed in Q4 2021.

As for the overall risk ratios, the top of the table hasn’t changed much since Q3’21 and is still occupied by Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Yemen, and Tajikistan. What has changed is their risk ratios have significantly increased. A similar risk ratio increase occurred for Japan and Portugal, even though in absolute value their risk ratio is still significantly lower than in the aforementioned countries. The most common botnets we saw in the wild are:

- Phorpiex

- BetaBot

- Tofsee

- Mykings

- MyloBot

- Nitol

- LemonDuck

- Emotet

- Dorkbot

- Qakbot

Adolf Středa, Malware Researcher

Coinminers

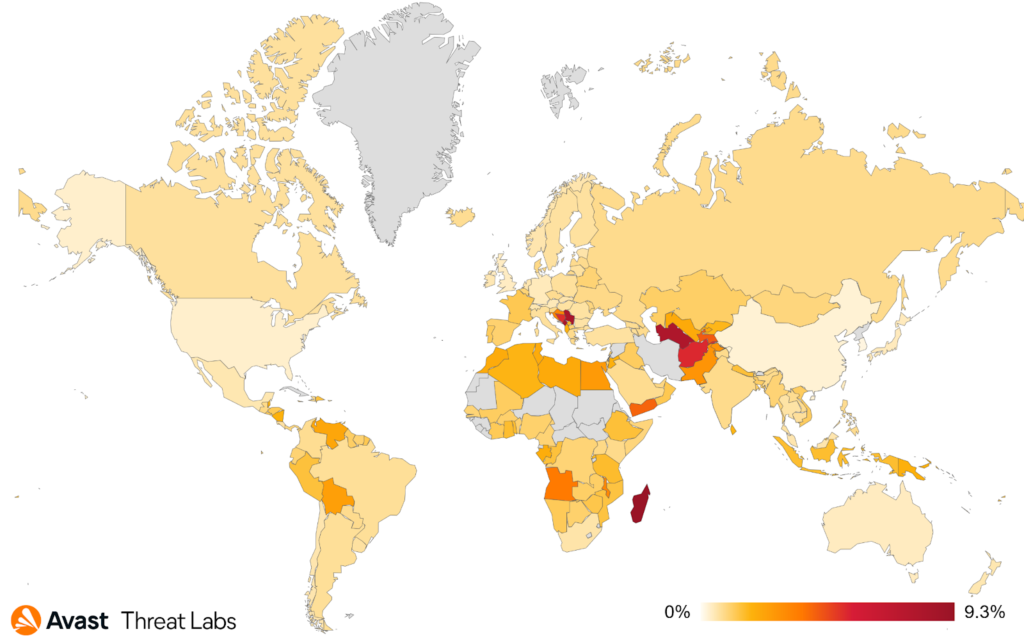

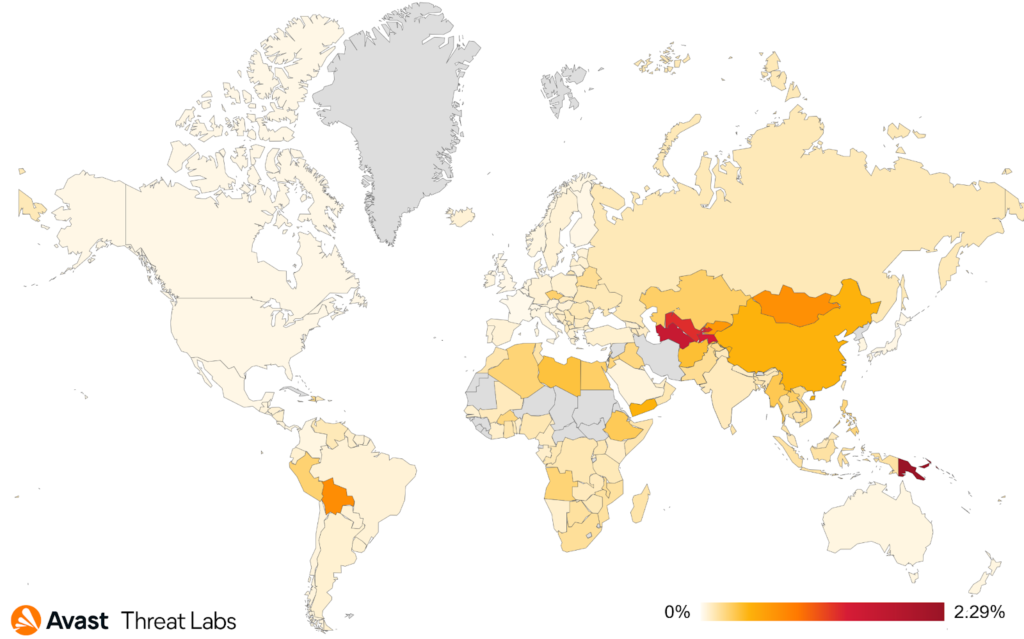

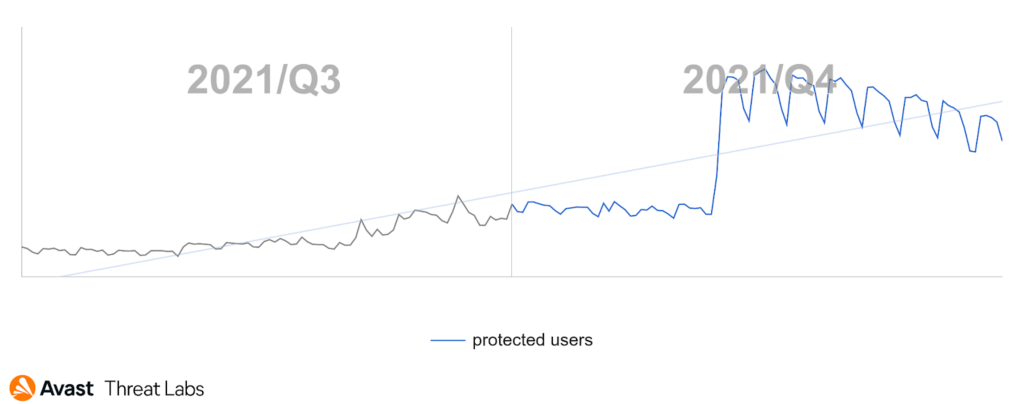

Even though cryptocurrencies experienced turbulent times, we actually saw an increase of malicious coin mining activity, it increased by a whooping 40% in our user base in Q4’21, as can be seen on the daily spreading chart below. This increase could be also influenced by the peak in Ethereum and Bitcoin prices in November.

The heat map below shows that in comparison to the previous quarter, there was a higher risk of a coin miner infection for users in Serbia and Montenegro. This is mainly due to a wider spreading of web miners in these regions, attempting to mine cryptocurrencies while the victim is visiting certain webpages. XMRig is still the leader choice among the popular coinminers.

CoinHelper is one of the prevalent coinminers that was still very active throughout Q4’21, mostly targeting users in Russia and the Ukraine. When the malware is executed on a victim’s system, CoinHelper downloads the notorious XMRig miner via the Tor network and starts to mine. Apart from coin mining, CoinHelper also harvests various information about its victims to recognize their geolocation, what AV solution they have installed, and what hardware they are using.

The malware is being spread in the form of a bundle with many popular applications, cracked software such as MS Office, games and game cheats like Minecraft and Cyberpunk 2077, or even clean installers, such as Google Chrome or AV products, as well as hiding in Windows 11 ISO image, and many others. The scope of the spreading is also supported by seeding the bundled apps via torrents, further abusing the unofficial way of downloading software.

Even though we observed multiple crypto currencies, including Ethereum or Bitcoin, configured to be mined, there was one particular type that stood out – Monero. Even though Monero is designed to be anonymous, thanks to the wrong usage of addresses and the mechanics of how mining pools work, we were able to get a deeper look into the malware authors’ Monero mining operation and find out that the total monetary gain of CoinHelper was 339,694.86 USD as of November, 29, 2021.

| Cryptocurrency | Earnings in USD | Earnings in cryptocurrency | Number of wallets |

| Monero | $292,006.08 | 1,216.692 [XMR] | 311 |

| Bitcoin | $46,245.37 | 0.800 [BTC] | 54 |

| Ethereum | $1,443.41 | 0.327 [ETH] | 5 |

Since the release of our CoinHelper blogpost, the miner was able to mine an additional ~15.162 XMR as of December 31, 2021 which translates to ~3,446.03 USD. With this calculation, we can say that at the turn of the year 2021, CoinHelper was still actively spreading, with the ability to mine ~0.474 XMR every day.

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

Jakub Kaloč, Malware Researcher

Information Stealers

In comparison with the previous quarters, we saw a slight decrease in information stealer in activity. The reason behind this is mainly a significant decrease in Fareit infections, which dropped by 61%. This places Fareit to sixth position from the previously dominant first rank, holding roughly 9% of the market share now. To this family, as well as to all the others, we wish a happy dropping in 2022!

The most prevalent information stealers in Q4’21 were AgentTesla, FormBook, and RedLine stealers. If you happen to get infected by an infostealer, there is almost a 50% chance that it will be one of these three.

Even though infostealers are traditionally popular around the world, there are certain regions where there is a greater risk of encountering one. Users in Singapore, Yemen, Turkey, and Serbia are most at risk of losing sensitive data. Out of these countries, we only saw an increase in risk ratio in Turkey when comparing the ratios to Q3’21.

Finally, malware strains based on Zeus still dominate the banking-trojan sector with roughly 40% in market share. However, one of these cases, the Citadel banker, experienced a significant drop in Q4’21, providing ClipBanker a space to grow.

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

LatAm Region

Latin America has always been an interesting area in malware research due to the unique and creative TTPs employed by multiple threat groups operating within this regional boundary. During Q4’21, a threat group called Chaes dominated Brazil’s threat landscape with infection attempts detected from more than 66,600 of our Brazilian customers. Compromising hundreds of WordPress web pages with Brazilian TLD, Chase serves malicious installers masquerading as Java Runtime Installers in Portuguese. Using a complex Python in-memory loading chain, Chaes installs malicious Google Chrome extensions onto victims’ machines. These extensions are capable of intercepting and collecting data from popular banking websites in Brazil such as Mercado Pago, Mercado Livre, Banco do Brasil, and Internet Banking Caixa.

Ousaban is another high-profile regional threat group whose operations in Brazil can be traced back to 2018. Getting massive attention in Q2’21 and Q3’21, Ousaban remains active during the Q4’21 period with infection attempts detected from 6,000+ unique users. Utilizing a technique called side-loading, Ousaban’s malicious payload is loaded by first executing a legitimate Avira application within a Microsoft Installer. The download links to these installers are mainly found in phishing emails which is Ousaban’s primary method of distribution.

Anh Ho, Malware Researcher

Igor Morgenstern, Malware Researcher

Ransomware

Let’s go back in time a little bit at first, before we dive into Q4’21 ransomware activity. In Q3’21, ransomware warfare was escalating, without a doubt. Most active strains were more prevalent than ever before. There were newspaper headlines about another large company being ransomed every other day, a massive supply-chain attack via MSP, record amounts of ransom payments, and sky-high self-esteem of cybercriminals.

While unfortunate, this havoc triggered a coordinated cooperation of nations, government agencies, and security vendors to hunt down ransomware authors and operators. The FBI, the U.S. Justice Department, and the U.S. Department of State started putting marks on ransomware gangs via multi-million bounties, the U.S. military acknowledged targeting cybercriminals who launch attacks on U.S. companies, and we even started witnessing actions by Russian officials. The most critical part was the busts of ransomware-group members by the FBI, Europol, and DoJ in Q4’21.

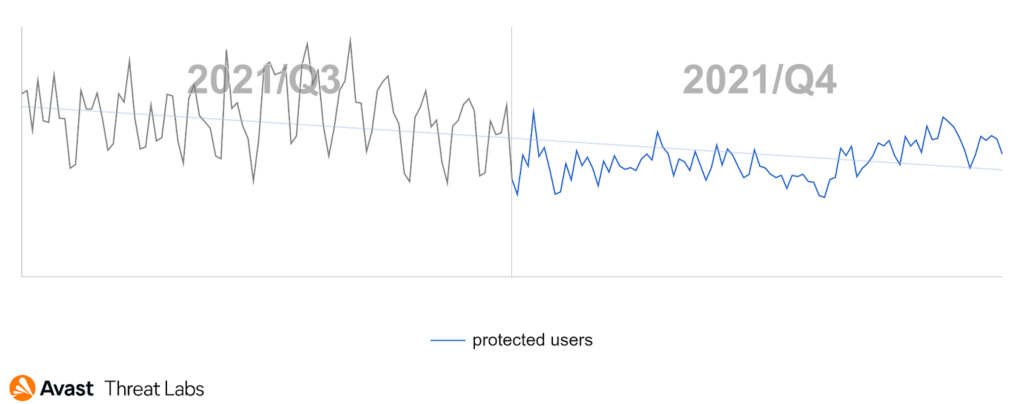

We believe all of this resulted in a significant decrease in ransomware attacks in Q4’21. In terms of the ransomware risk ratio, it was lower by an impressive 28% compared to Q3’21. We hope to see a continuation of this trend in Q1’22, but we are also prepared for the opposite.

The positive decrease of the risk ratio Q/Q was evident in the majority of countries where we have our telemetry, with a few exceptions such as Bolivia, Uzbekistan, and Mongolia (all with more than +400% increase), Kazakhstan and Belarus (where the risk ratio doubled Q/Q), Russia (+49%), Slovakia (+37%), or Austria (+25%).

The most prevalent strains from Q3’21 either vanished or significantly decreased in volume in Q4’21. For example, the operators and authors of the DarkMatter ransomware went silent, most probably because a $10 million bounty was put on their heads by the FBI. Furthermore, STOP ransomware, which was the most prevalent strain in Q3’21, was still releasing new variants regularly to lure users seeking pirated software, but the number of targeted (and protected) users dropped by 58% and its “market share” decreased by 36%. Another strain worth mentioning was Sodinokibi aka REvil – its presence decreased by 50% in Q4’21 and it will be interesting to monitor its future presence because of the circumstances happening in Q1’22 (greetings to Sodinokibi/REvil gang members currently sitting custody).

The most prevalent ransomware strains in Q4’21:

- STOP

- WannaCry

- Sodinokibi

- Conti

- CrySiS

- Exotic

- Makop

- GlobeImposter

- GoRansomware

- VirLock

Not everything ransomware related was positive in Q4’21. For example, new strains were discovered that could quickly emerge in prevalence, such as BlackCat (aka ALPHV) with its RaaS model introduced on darknet forums or a low-quality Khonsari ransomware, which took the opportunity to be the first ransomware exploiting the aforementioned Log4j vulnerability and thus beating the Conti in this race.

Last, but not least, I would like to mention new free ransomware decryption tools we’ve released. This time for AtomSilo, LockFile, and Babuk ransomware. AtomSilo is not the most prevalent strain, but it has been constantly spreading for more than a year. So we were happy as our decryptor immediately started helping ransomware victims.

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Remote Access Trojans (RATs)

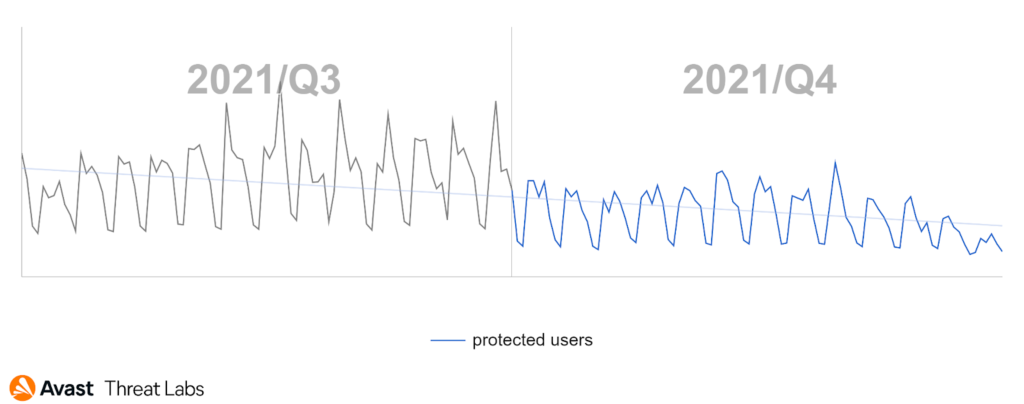

The last weeks of Q4’21 are also known as “days of peace and joy” and this claim also applies for malicious actors. As you can see in the graph below of RAT activity for this quarter, it is obvious that malware actors are just people and many of them took holiday breaks, that’s probably why the activity level during the end of December more than halved. The periodical drops that can be seen are weekends as most campaigns usually appear from Monday to Thursday.

In the graph below, we can see a Q3/Q4 comparison of the RAT activity.

The heat map below shines with multiple colors like a Christmas tree and among the countries with the highest risk ratio we see Czech Republic, Singapore, Serbia, Greece, and Croatia. We also detected a high Q/Q increase of the risk ratio in Slovakia (+39%), Japan (+30%), and Germany (+23%).

Most prevalent RATs in Q4’21:

- Warzone

- njRAT

- Remcos

- NanoCore

- AsyncRat

- QuasarRAT

- NetWire

- SpyNet

- DarkComet

- DarkCrystal

The volume of attacks and protected users overall was similar to what we saw in Q3’21, but there was also an increase within families, such as Warzone or DarkCrystal (their activity more than doubled), SpyNet (+89%) and QuasarRAT(+21%).

A hot topic this quarter was a vulnerability in Log4j and in addition to other malware types, some RATs were also spread thanks to the vulnerability. The most prevalent were NanoCore, AsyncRat and Orcus. Another new vulnerability that was exploited by RATs was CVE-2021-40449. This vulnerability was used to elevate permissions of malicious processes by exploiting the Windows kernel driver. Attackers used this vulnerability to download and launch the MistarySnail RAT. Furthermore, a very important cause of high Nanocore and AsyncRat detections was caused by a malicious campaign abusing the cloud providers, Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Service (AWS). In this campaign malware attackers used Azure and AWS as download servers for their malicious payloads.

But that’s not all, at the beginning of December we found a renamed version of DcRat under the name SantaRat. This renamed version was just pure copy-paste of DcRat, but it shows that malware developers were also in the Christmas spirit and maybe they also hoped that their version of Santa would visit many households as well, to deliver their gift. To be clear, DcRat is a slightly modified version of AsyncRat.

The developers of DcRat weren’t the only ones playing the role of Santa and distributing gifts. Many other malware authors also delivered RAT related gifts to us in Q4’21.

The first one was the DarkWatchman RAT, written in JavaScript and on top of the programming language used, it differs from other RATs with one other special property: it lives in the system registry keys. This means that it uses registry keys to store its code, as well as to store temporary data, thus making it fileless.

Another RAT that appeared was ActionRAT, released by the SideCopy APT group in an attack on the government of Afghanistan. This RAT uses base64 encoding to obfuscate its strings and C&C domains. Its capabilities are quite simple, but still powerful so it could execute commands from a C&C server, upload, download and execute files, and retrieve the victim’s machine details.

We also observed two new RATs spread on Linux systems. CronRAT's name already tells us what it uses under the hood, but for what? This RAT uses cron jobs, which are basically scheduled tasks on Linux systems to store payloads. These tasks were scheduled on 31.2. (a non-existent date) and that’s why they were not triggered, so the payload could remain hidden. The second RAT from the Linux duo was NginRAT which was found on servers that were previously infected with CronRAT and served the same purpose: to provide remote access to the compromised systems.

Even though we saw a decrease in RAT activity at the end of December it won’t stay that way. Malicious actors will likely come back from their vacations fresh and will deliver new surprises. So stay tuned.

Samuel Sidor, Malware Researcher

Rootkits

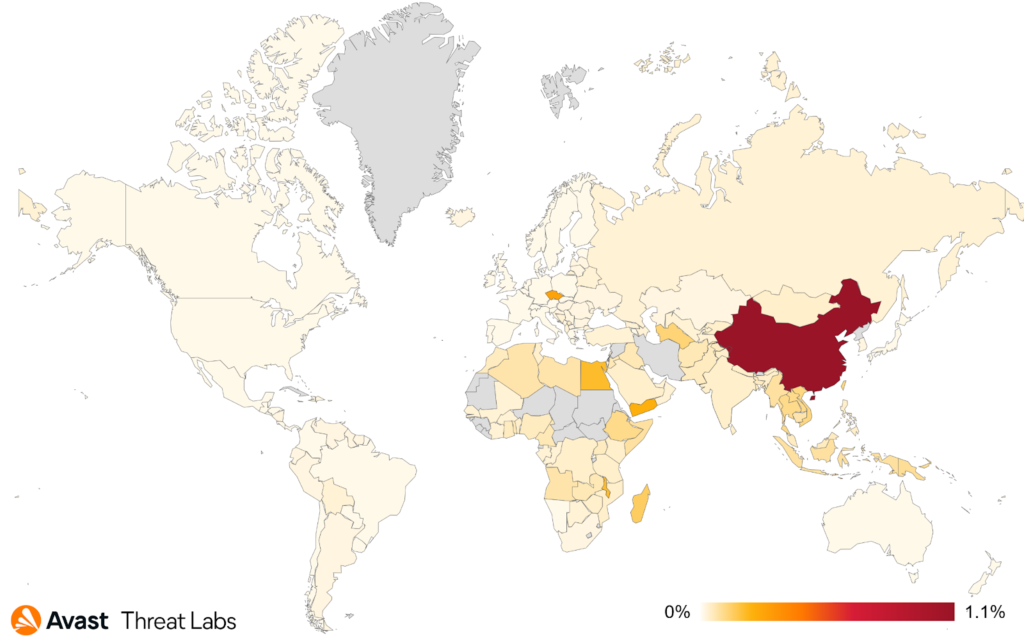

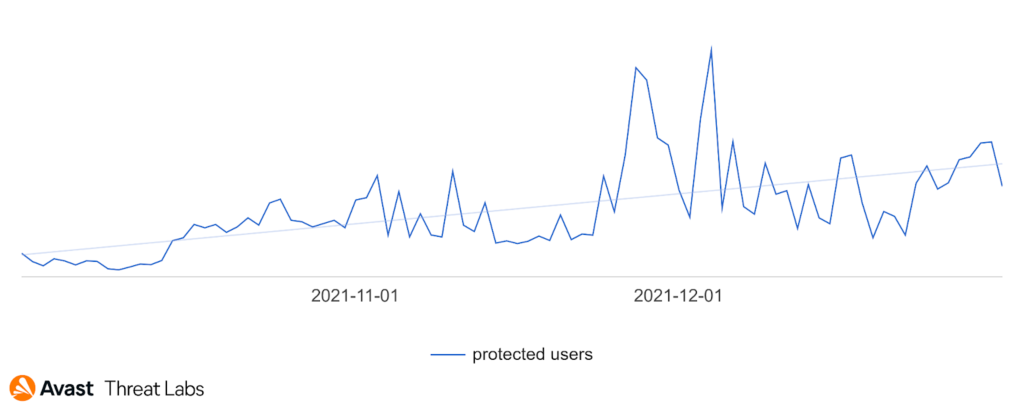

We have recorded a significant increase in rootkit activity at Q4’21, illustrated in the chart below. This phenomenon can be explained by the increase in adware activity since the most active rootkit was the Cerbu rootkit. The primary function of Cerbu is to hijack browser homepages and redirect site URLs according to the rootkit configuration. So, this rootkit can be easily deployed and configured for adware.

The graph below shows that China is still the most at risk countries in terms of protected users, although attacks in China decreased by about 17%.

In Q4’21, the most significant increase of risk ratio was in Egypt and Vietnam. On the other hand, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China reported approximately the same values as in the previous quarter. The most protected users were in the Czech Republic, Russian Federation, China, and Indonesia.

Martin Chlumecký, Malware Researcher

Technical support scams (TSS)

During the last quarter, we registered a significant wave of increased tech support scam activity. In Q4’21, we saw peaks at the end of December and we are already seeing some active spikes in January.

Activity of a long-term TSS campaign

The top targeted countries for this campaign are the United States, Brazil, and France. The activity of this campaign shows the tireless effort of the scammers and proves the increasing popularity of this threat.

In combination with other outgoing long-term campaigns, our data also shows two high spikes of activity of another campaign, lasting no longer than a few days, heavily targeting the United States and Canada, as well as other countries in Europe. This campaign had its peak at the end of November and the beginning of December, then it slowly died out.

Rise and fall and slow fall of the second campaign

Example of a typical URL for this short campaign:

hxxp://159.223.148.40/ViB888Code0MA888Error0888HElp008ViB700Vi/index.html

hxxp://157.245.222.59/security-alert-attention-dangerous-code-65296/88WiLi88Code9fd0CH888Error888HElp008700/index.html

We also noticed attempts at innovation as new variants of TSS samples appeared. So, not just a typical locked browser with error messages but other imitations like Amazon Prime, and PayPal. We are of course tracking these new variants and will see how popular they will be in the next quarter.

Alexej Savčin, Malware Analyst

Vulnerabilities and Exploits

As was already mentioned in the foreword, the vulnerability news in Q4’21 was dominated by Log4Shell. This vulnerability in Log4j – a seemingly innocent Java logging utility – took the infosec community by storm. It was extremely dangerous because of the ubiquity of Log4j and the ease of exploitation, which was made even easier by several PoC exploits, ready to be weaponized by all kinds of attackers. The root of the vulnerability was an unsafe use of JNDI lookups, a vulnerability class that Hewlett Packard researchers Alvaro Muñoz and Oleksandr Mirosh already warned about in their 2016 BlackHat talk. Nevertheless, the vulnerability existed in Log4j from 2013 until 2021, for a total of eight years.

For the attackers, Log4Shell was the greatest thing ever. They could just try to stuff the malicious string into whatever counts as user input and observe if it gets logged somewhere by a vulnerable version of Log4j. If it does, they just gained remote code execution in the absence of any mitigations. For the defenders on the other hand, Log4Shell proved to be a major headache. They had to find all the software in their organization that is (directly or indirectly) using the vulnerable utility and then patch it or mitigate it. And they had to do it fast, before the attackers managed to exploit something in their infrastructure. To make things even worse, this process had to be iterated a couple of times, because even some of the patched versions of Log4j turned out not to be that safe after all.

From a research standpoint, it was interesting to observe the way the exploit was adopted by various attackers. First, there were only probes for the vulnerability, abusing the JNDI DNS service provider. Then, the first attackers started exploiting Log4Shell to gain remote code execution using the LDAP and RMI service providers. The JNDI strings in-the-wild also became more obfuscated over time, as the attackers started to employ simple obfuscation techniques in an attempt to evade signature-based detection. As time went on, more and more attackers exploited the vulnerability. In the end, it was used to push all kinds of malware, ranging from simple coinminers to sophisticated APT implants.

In other vulnerability news, we continued our research into browser exploit kits. In October, we found that Underminer implemented an exploit for CVE-2021-21224 to join Magnitude in attacking unpatched Chromium-based browsers. While Magnitude stopped using its Chromium exploit chain, Underminer is still using it with a moderate level of success. We published a detailed piece of research about these Chromium exploit chains, so make sure to read it if you’d like to know more.

Jan Vojtěšek, Malware Researcher

Web skimming

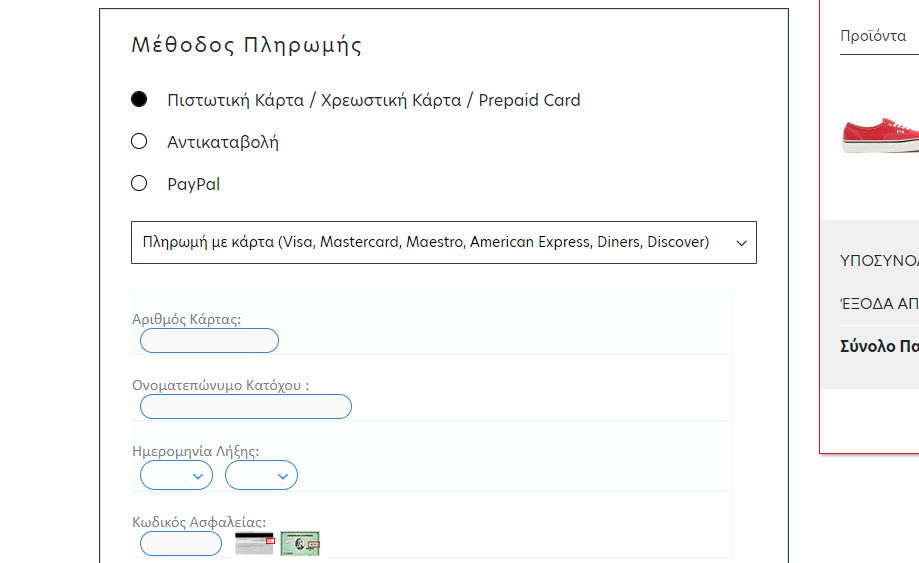

One of the top affected countries by web skimming in Q4’21 was Saudi Arabia, in contrast with Q3’21 we protected four times as many users in Saudi Arabia in Q4. It was caused by an infection of e-commerce sites souqtime[.]com and swsg[.]co. The latter loads malicious code from dev-connect[.]com[.]de. This domain can be connected to other known web skimming domains via common IP 195[.]54[.]160[.]61. The malicious code responsible for stealing credit card details loads only on the checkout page. In this particular case, it is almost impossible for the customer to recognize that the website is compromised, because the attacker steals the payment details from the existing payment form. The payment details are then sent to the attackers website via POST request with custom encoding (multiple base64 and substitution). The data sending is triggered on an “onclick” event and every time the text from all input fields is sent.

In Australia the most protected users were visitors of mobilitycaring[.]com[.]au. During Q4’21 this website was sending payment details to two different malicious domains, first was stripe-auth-api[.]com, and later the attacker changed it to booctstrap[.]com. This domain is typosquatting mimicking bootstrap.com. This is not the first case we observed where an attacker changed the exfiltration domain during the infection.

In Q4’21, we protected nearly twice as many users in Greece as in Q3’21. The reason behind this was the infected site retro23[.]gr, unlike the infected site from Saudi Arabia (swsg[.]co), in this case the payment form is not present on the website, therefore the attacker inserted their own. But as we can see in the image below, that form does not fit into the design of the website. This gives customers the opportunity to notice that something is wrong and not fill in their payment details. We published a detailed analysis about web skimming attacks, where you can learn more.

Pavlína Kopecká, Malware Analyst

Mobile

Premium SMS – UltimaSMS

Scams that siphon victims’ money away through premium SMS subscriptions have resurfaced in the last few months. Available on the Play Store, they mimic legitimate applications and games, often featuring catchy adverts. Once downloaded, they prompt the user to enter their phone number to access the app. Unbeknownst to the user, they are then subscribed to a premium SMS service that can cost up to $10 per week.

As users often aren’t inherently familiar with how recurring SMS subscriptions work, these scams can run for months unnoticed and cause an expensive phone bill for the victims. Uninstalling the app doesn’t stop the subscription, the victim has to contact their provider to ensure the subscription is properly canceled, adding to the hassle these scams create.

Avast has identified one such family of Premium SMS scams – UltimaSMS. These applications serve only to subscribe victims to premium SMS subscriptions and do not have any further functions. The actors behind UltimaSMS extensively used social media to advertise their applications and accrued over 10M downloads as a result.

According to our data the most targeted countries were those in the Middle East, like Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia or Kuwait. Although we’ve seen instances of these threats active even in other areas, like Europe, for instance in our home country – the Czech Republic. We attribute this widespread reach of UltimaSMS to its former availability on the Play Store and localized social media advertisements.

Jakub Vávra, Malware Analyst

Spyware – Facestealer

A newcomer this year, Facestealer, resurfaced on multiple occasions in Q4’21. It is a spyware that injects JavaScript into the inbuilt Android Webview browser in order to steal Facebook credentials. Masquerading as photo editors, horoscopes, fitness apps and others, it has been a continued presence in the last few months of 2021 and it appears to be here to stay.

Facestealer apps look legitimate at first and they fulfill their described app functions. After a period of time, the apps’ C&C server sends a command to prompt the user to sign in to Facebook to continue using the app, without adverts. Users may have their guard down as they’ve used the app without issue up until now. The app loads the legitimate Facebook login website and injects malicious JS code to skim the users’ login credentials. The user may be unaware their social media account has been breached.

It is likely that, as with other spyware families we’ve seen in the past, Facestealer will be reused in order to target other social media platforms or even banks. The mechanism used in the initial versions can be adjusted as the attackers can load login pages from potentially any platform.

According to our threat data, this threat was mostly targeting our users in Africa and surrounding islands – Niger and Nigeria in the lead, followed by Madagascar, Zimbabwe and others.

Jakub Vávra, Malware Analyst

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Fake Covid themed apps on the decline

Despite the pandemic raging on and governments implementing various new measures and introducing new applications such as Covid Passports, there’s been a steady decline in the number of fake Covid apps. Various bankers, spyware and trojans that imitated official Covid apps flooded the mobile market during 2020 and first half of 2021, but it seems they have now returned to disguising themselves as delivery apps, utility apps and others that we have seen before.

It’s possible that users aren’t as susceptible to fake Covid apps anymore or that the previous methods of attack proved more efficient for these pieces of malware, as evidenced for example on the massively successful campaigns of FluBot, which we reported on previously. Cerberus/Alien variants stood out as the bankers that were on the frontlines of fake Covid-themed apps. But similarly to some of this year’s newcomers such as FluBot or Coper bankers, the focus has now shifted back to the “original” attempts to breach users’ phones through SMS phishing while pretending to be a delivery service app, bank app or others.

During the beginning of the pandemic we were able to collect hundreds to thousands of new unique samples monthly disguising themselves as various apps connected to providing Covid information, Covid passes, vaccination proofs or contact tracing apps or simply just inserting the Covid/Corona/Sars keywords in their names or icons. During the second half of 2021 this trend has been steadily dropping. In Q4’21 we have seen only low 10s of such new samples.

Jakub Vávra, Malware Analyst

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Acknowledgements / Credits

Malware researchers

- Adolf Středa

- Alex Savčin

- Anh Ho

- Daniel Beneš

- Igor Morgenstern

- Jakub Kaloč

- Jakub Křoustek

- Jakub Vávra

- Jan Rubín

- Jan Vojtěšek

- Luigino Camastra

- Martin Hron

- Martin Chlumecký

- Michal Salát

- Ondřej David

- Pavlína Kopecká

- Samuel Sidor

Data analysts

- Pavol Plaskoň

Communications

- Stefanie Smith