We have found a new targeted attack against a small, lesser-known U.S. federal government commission associated with international rights. Despite repeated attempts through multiple channels over the course of months to make them aware of and resolve this issue they would not engage.

After initial communication directly to the affected organization, they would not respond, return communications or provide any information.

The attempts to resolve this issue included repeated direct follow up outreach attempts to the organization. We also used other standard channels for reporting security issues directly to affected organizations and standard channels the United States Government has in place to receive reports like this.

In these conversations and outreach we have received no follow up or information on whether the issues we reported have been resolved and no further information was shared with us.

Because of the lack of discernible action or response, we are now releasing our findings to the community so they can be aware of this threat and take measures to protect their customers and the community. We are not naming the entity affected beyond this description.

Because they would not engage with us, we have limited information about the attack. We are unable to attribute the attack, its impact, or duration. We are only able to describe two files we observed in the attack. In this blog, we are providing our analysis of these two files.

While we have no information on the impact of this attack or the actions taken by the attackers, based on our analysis of the files in question, we believe it’s reasonable to conclude that the attackers were able to intercept and possibly exfiltrate all local network traffic in this organization. This could include information exchanged with other US government agencies and other international governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) focused on international rights. We also have indications that the attackers could run code of their choosing in the operating system’s context on infected systems, giving them complete control.

Taken altogether, this attack could have given total visibility of the network and complete control of a system and thus could be used as the first step in a multi-stage attack to penetrate this, or other networks more deeply.

Overview of the Two Files Found

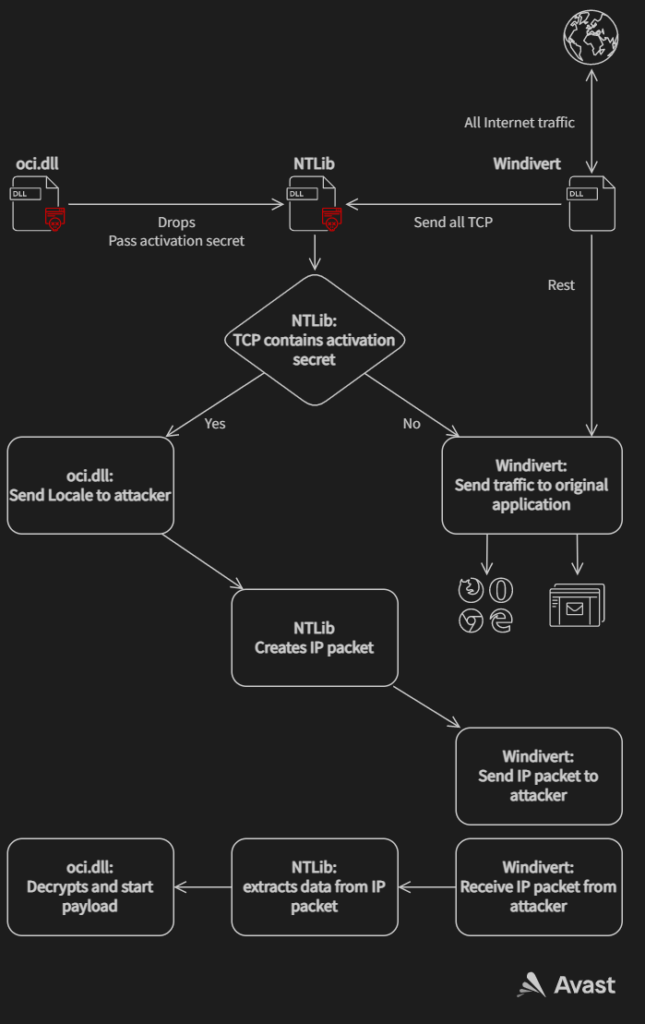

The first file masquerades as oci.dll and abuses WinDivert, a legitimate packet capturing utility, to listen to all internet communication. It allows the attacker to download and run any malicious code on the infected system. The main scope of this downloader may be to use priviliged local rights to overcome firewalls and network monitoring.

The second file also masquerades as oci.dll, replacing the first file at a later stage of the attack and is a decryptor very similar to the one described by Trend Labs from Operation red signature. In the following text we present analysis of both of these files, describe the internet protocol used and demonstrate the running of any code on an infected machine.

First file – Downloader

We found this first file disguised as oci.dll (“C:\Windows\System32\oci.dll”) (Oracle Call Interface). It contains a compressed library (let us call it NTlib). This oci.dll exports only one function DllRegisterService. This function checks the MD5 of the hostname and stops if it doesn’t match the one it stores. This gives us two possibilities. Either the attacker knew the hostname of the targeted device in advance or the file was edited as part of the installation to run only on an infected machine to make dynamic analysis harder.

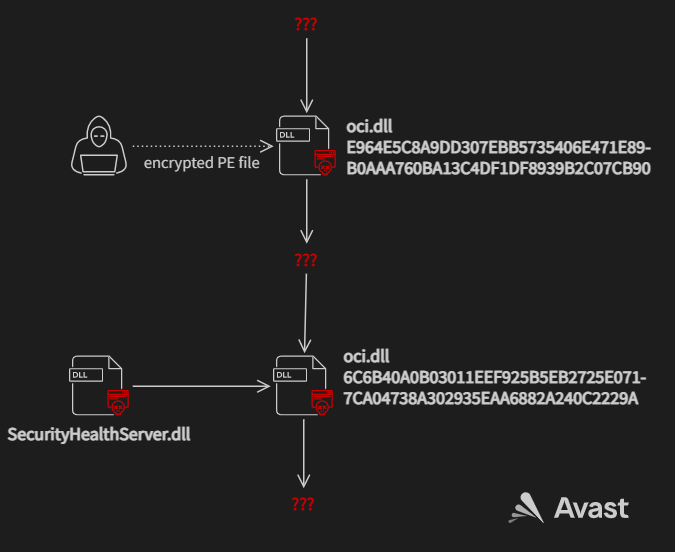

We found two samples of this file:

| SHA256 | Description |

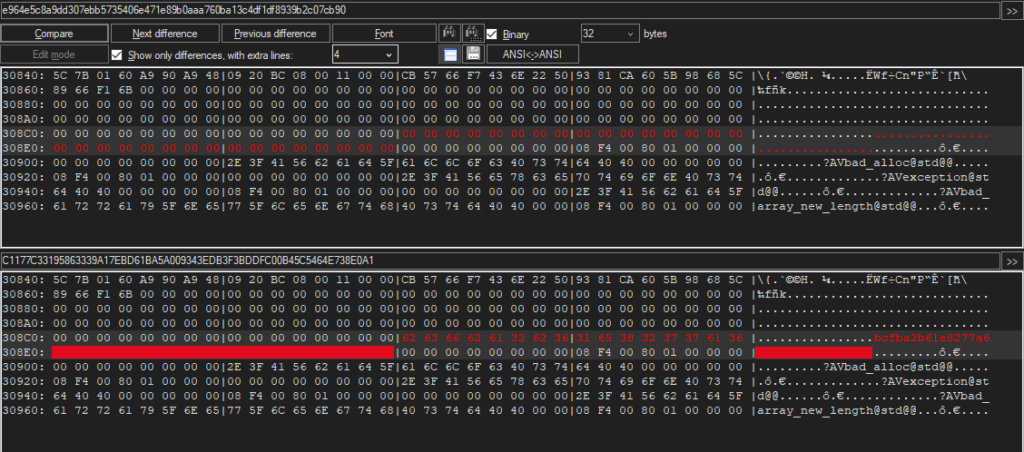

| E964E5C8A9DD307EBB5735406E471E89B0AAA760BA13C4DF1DF8939B2C07CB90 | has no hash stored and it can run on every PC |

| C1177C33195863339A17EBD61BA5A009343EDB3F3BDDFC00B45C5464E738E0A1 | is exactly the same file but it contains the hash of hostname |

Oci.dll then decompresses and loads NTlib and waits for the attacker to send a PE file, which is then executed.

NTlib works as a layer between oci.dll and WinDivert.

The documentation for WinDivert describes it as “a powerful user-mode capture/sniffing/modification/blocking/re-injection package for Windows 7, Windows 8 and Windows 10. WinDivert can be used to implement user-mode packet filters, packet sniffers, firewalls, NAT, VPNs, tunneling applications, etc., without the need to write kernel-mode code.”

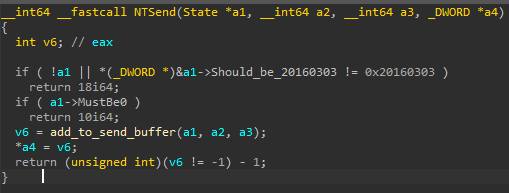

NTlib creates a higher level interface for TCP communication by using low-level IP packets oriented functions of WinDivert. The NTLib checks if the input has magic bytes 0x20160303 in a specific position of the structure given as the first argument as some sort of authentication.

Exported functions of NTLib are:

- NTAccept

- NTAcceptPWD

- NTSend

- NTReceive

- NTIsClosed

- NTClose

- NTGetSrcAddr

- NTGetDscAddr

- NTGetPwdPacket

The names of the exported functions are self-explanatory. The only interesting function is NTAcceptPWD, which gets an activation secret as an argument and sniffs all the incoming TCP communication, searching for communication with that activation secret. It means that the malware itself does not open any port on its own, it uses the ports open by the system or other applications for its communication. The malicious communication is not reinjected to the Windows network stack, therefore the application listening on that port does not receive it and doesn’t even know some traffic to its port is being intercepted.

The oci.dll uses NTlib to find communications with the activation secret CB 57 66 F7 43 6E 22 50 93 81 CA 60 5B 98 68 5C 89 66 F1 6B. While NTlib captures the activation secret, oci.dll responds with Locale (Windows GUID, OEM code page identifier and Thread Locale) and then waits for the encrypted PE file that exports SetNtApiFunctions. If the PE file is correctly decrypted, decompressed and loaded, it calls the newly obtained function SetNtApiFunctions.

The Protocol

As we mentioned before, the communication starts with the attacker sending CB 57 66 F7 43 6E 22 50 93 81 CA 60 5B 98 68 5C 89 66 F1 6B (the activation secret) over TCP to any open port of the infected machine.

The response of the infected machine:

- Size of the of the message – 24 (value: 28) [4 B]

- Random encryption key 1 [4 B]

- Encrypted with Random encryption key 1 and precomputed key:

- 0 [4 B]

- ThreadLocale [4 B]

- OEMCP or 0 [4 B]

- 0x20160814 (to test correctness of decryption) [4 B]

- 0,2,0,64,0,0,0 [each 4 B]

The encryption is xor cipher with precomputed 256 B key:

5C434846474C3F284EB64A4343433B4031E546C049584747454956FE4C51B369595AA5DB6DA082696E6C6D72654E74DC706969696166570B6CE66F7E6D6D6B6F7C247277D98F7F80CB0193C6A88F949293988B749A02968F8F8F878C7D31920C95A493939195A24A989DFFB5A5A6F127B9ECCEB5BAB8B9BEB19AC028BCB5B5B5ADB2A357B832BBCAB9B9B7BBC870BEC325DBCBCC174DDF12F4DBE0DEDFE4D7C0E64EE2DBDBDBD3D8C97DDE58E1F0DFDFDDE1EE96E4E94B01F1F23D7305381A010604050AFDE60C7408010101F9FEEFA3047E07160505030714BC0A0F7127171863992B5E40272C2A2B30230C329A2E2727271F2415C92AA42D3C2B2B292D3AE2

That is xored with another 4 B key.

After sending the above message the infected machine awaits for a following message with the encrypted PE file mentioned above:

- Size of the of the message – 24 [4 B]

- Random Encryption key 2 [4 B]

- Encrypted with Random encryption key 2 and precomputed key:

- 6 (LZO level?) [4 B]

- 0 [8 B]

- 0x20160814 [4 B]

- 0x20160814 [4 B]

- Size of the whole message [4 B]

- Offset (0) [4 B]

- Length (Size of the whole message) [4 B]

- Encrypted with key 0x1415CCE and precomputed key:

- 0 [16 B]

- Length of decompressed PE file [4 B]

- 0 [16 B]

- Length of decompressed PE file [4 B]

- 0 [16 B]

- LZO level 6 compressed PE file

With the same encryption as the previous message.

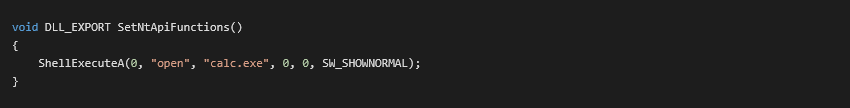

In our research we were unable to obtain the PE file that is part of this attack. In our analysis, we demonstrated the code execution capabilities by using a library with the following function:

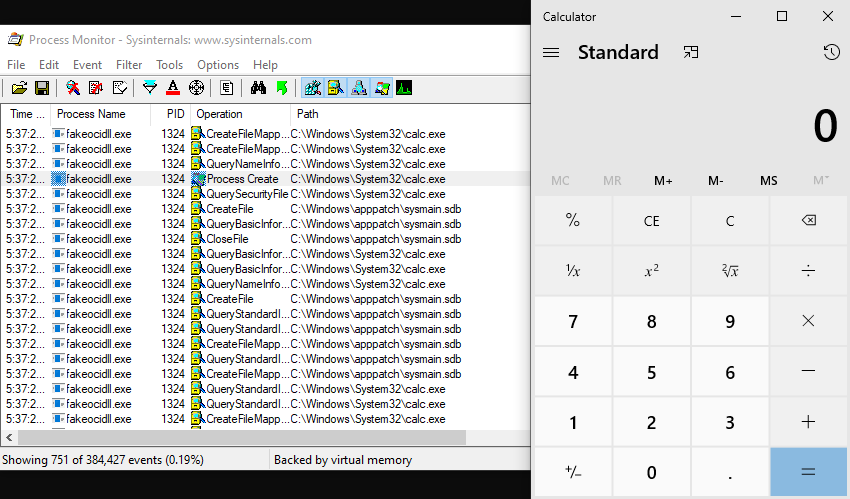

In a controlled lab setting, we were able to start the calculator on an infected machine over the network with the following python script (link to GitHub).

Second File – Decryptor

The second file we found also masquerages as oci.dll. This file replaced the first downloader oci.dll and likely represents another, later stage of the same attack. The purpose of this file is to decrypt and run in memory the file “SecurityHealthServer.dll”.

SHA256: 6C6B40A0B03011EEF925B5EB2725E0717CA04738A302935EAA6882A240C2229A

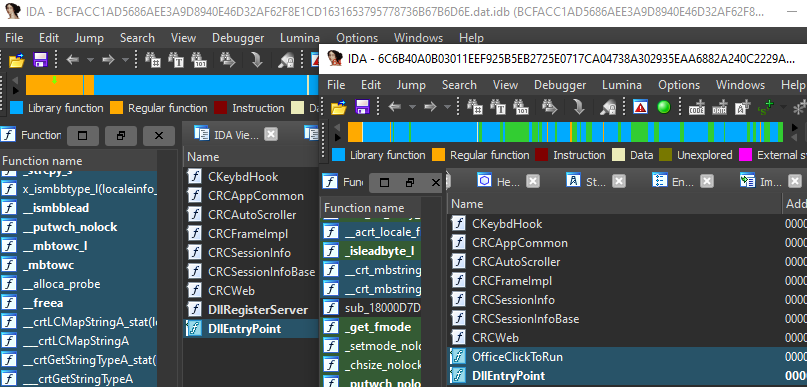

We found that this file is similar to the rcview40u.dll that was involved in Operation Red Signature. rcview40u.dll (bcfacc1ad5686aee3a9d8940e46d32af62f8e1cd1631653795778736b67b6d6e) was signed by a stolen certificate and distributed to specific targets from a hacked update server. It decrypted a file named rcview40.log, that contained 9002 RAT and executed it in memory.

This oci.dll exports same functions as rcview40u.dll:

The new oci.dll decrypts SecurityHealthServer.dll with RC4 and used the string TSMSISRV.dll as the encryption key. This is similar to what we’ve seen with rcview40u.dll which also uses RC4 to decrypt rcview.log with the string kernel32.dll as the encryption key.

Because of the similarities between this oci.dll and rcview40u.dll, we believe it is likely that the attacker had access to the source code of the three year-old rcview40u.dll. The newer oci.dll has minor changes like starting the decrypted file in a new thread instead of in a function call which is what rcview40u.dll does. oci.dll was also compiled for x86-64 architecture while rcview40u.dll was only compiled for x86 architecture.

Conclusion

While we only have parts of the attack puzzle, we can see that the attackers against these systems were able to compromise systems on the network in a way that enabled them to run code as the operating system and capture any network traffic travelling to and from the infected system.

We also see evidence that this attack was carried out in at least two stages, as shown by the two different versions of oci.dll we found and analyzed.

The second version of the oci.dll shows several markers in common with rcview40u.dll that was used in Operation Red Signature such that we believe these attackers had access to the source code of the malware used in that attack.

Because the affected organization would not engage we do not have any more factual information about this attack. It is reasonable to presume that some form of data gathering and exfiltration of network traffic happened, but that is informed speculation. Further because this could have given total visibility of the network and complete control of an infected system it is further reasonable speculation that this could be the first step in a multi-stage attack to penetrate this, or other networks more deeply in a classic APT-type operation.

That said, we have no way to know for sure the size and scope of this attack beyond what we’ve seen. The lack of responsiveness is unprecedented and cause for concern. Other government and non-government agencies focused on international rights should use the IoCs we are providing to check their networks to see if they may be impacted by this attack as well.