Latest Avast Q3’21 Threat Report reveals elevated risk for ransomware and RAT attacks, rootkits and exploit kits return.

Foreword

The threat landscape is a fascinating environment that is constantly changing and evolving. What was an unshakeable truth for a long time is no longer valid the next day; the most prevalent threats suddenly disappear, but are usually quickly replaced by at least two new ones; or that the bad guys standing behind these threats always come with new techniques when trying to get their profit.

Together with my colleagues, we came to the conclusion that it would be selfish to keep our insight into this landscape just for ourselves so we decided to start with publishing periodic Avast threat reports. Here, we would like to share with you details about emerging threats, stories behind malware strains and their spreading, and of course stats from our 435M+ endpoints telemetry.

So let us start with the Q3 report, and I must say it was a juicy quarter. To give you a sneak peak of the report: My colleagues published details about an ongoing APT campaign targeting the Mongolian certification authority MonPass. Another novel research was the discovery of the Crackonosh crypto stealer that earned more than $2 million USD to its operators. We were also intently monitoring which botnet will replace the previous kingpin Emotet in Q3. Furthermore, there was a rampant spreading of banking trojans on mobile (especially FluBot) and rootkits on Windows almost doubled their activity in September compared to the previous period. And for me, it started on July 2 at night with the Sodinokibi/REvil ransomware supply chain attack on the Kaseya MSP, it abused Microsoft Defender, there was involvement of world leaders, and precise timing (happening during my threat labs duty – respect to all infosec fellows that were dealing with that on this Independence weekend). As I said – it’s a fascinating environment…

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Methodology

This report is structured as two main sections – Desktop, informing about our intel from Windows, Linux, and MacOS, and Mobile, where we inform about Android and iOS threats.

Furthermore, we use the term risk ratio in this report for informing about the severity of particular threats, which is calculated as a monthly average of “Number of attacked users / Number of active users in a given country”. Unless stated otherwise, the risk is available just for countries with more than 10,000 active users per month.

Desktop

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)

In Q3 of 2021, we saw APT activity on several fronts: continued attacks against Certificate Authorities (CAs), the Gamaredon group targeting military and government targets, and campaigns in Southeast Asia.

Certificate Authorities (CAs) are always of increased interest to APT groups for multiple reasons. By their very nature CAs have a high level of trust, they often provide services to the government organisations or being a part of one themselves, making them a perfect target for supply chain attacks. A well-known example was the targeting of the Vietnam Government Certification Authority in 2020. In Q3 Avast also wrote about activity targeting the Mongolian CA MonPass.

At the very beginning of Q3, Avast researchers discovered and published a story about an installer downloaded from the official website of Monpass, a major certification authority (CA) in Mongolia in East Asia that was backdoored with Cobalt Strike binaries.

A public web server hosted by Monpass was breached potentially eight separate times: we found eight different webshells and backdoors on this server. The MonPass client available for download from 8 February 2021 until 3 March 20 2021 was backdoored. Adversaries used steganography to decrypt and implant Cobalt Strike beacons.

Additionally during the last few months we’ve seen an increased activity of the Gamaredon group primarily in Ukraine. The main targets of the group remain military and government institutions. The group keeps utilizing old techniques it’s been using for years in addition to a few new tools in their arsenal. Malware associated with Gamaredon was among the most prevalent between APT groups we tracked in this quarter.

Groups operating in Southeast and East Asia were active during this period as well. We’ve seen multiple campaigns in Myanmar, Philippines, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The majority of the actors in the region can be identified as Chinese-speaking groups. Technique of choice among these groups remains sideloading. We’ve seen samples with main functionality to search for potential candidates for sideloading on a victim’s machine, so they are not going to abandon this technique anytime soon.

Luigino Camastra, Malware Researcher

Igor Morgenstern, Malware Researcher

Michal Salát, Threat Intelligence Director

Bots

Old botnets still haven’t said their last word. After Emotet’s takedown at the start of 2021, Trickbot has been aspiring to become its successor. Moreover, despite numerous takedown attempts, Trickbot is still thriving. Qakbot came up with a rare change in its internal payload which brought restructured resources. As for Ursnif (aka Gozi), the activity in Q3 kept its usual pace – with new webinjects and new builds being continuously released. However, Ursnif’s targets remain largely the same – European, and especially Italian, banks and other financial organisations. Surprisingly, Phorpiex seemed to maintain its presence, even though its source code has been reported to be on sale in August. This is especially true for Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Yemen where Phorpiex is especially prolific, significantly contributing to their above-average risk ratio.

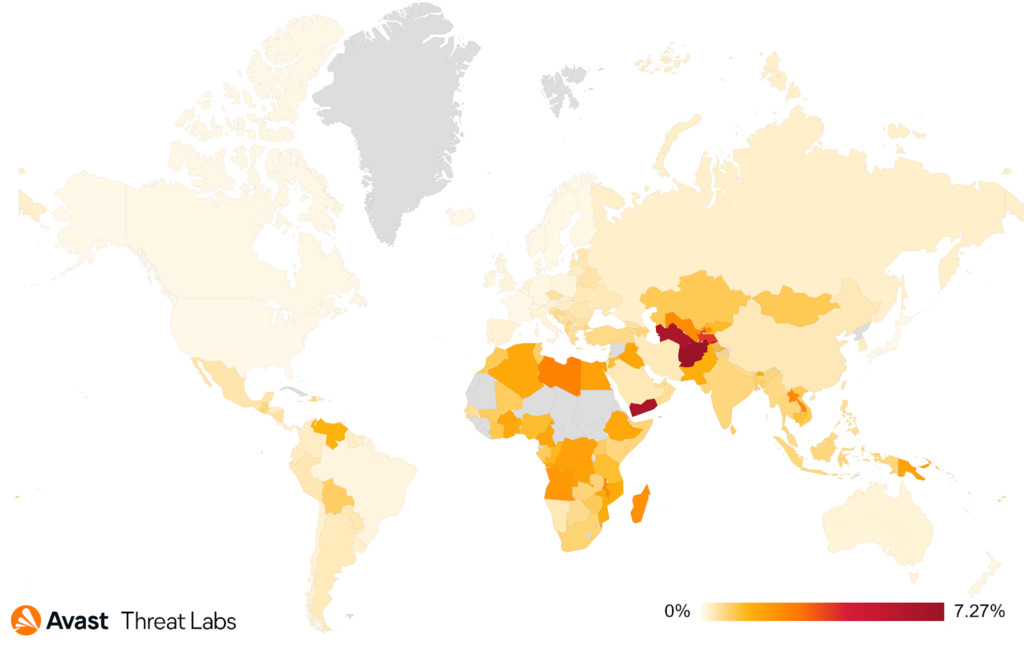

Below is a heatmap showing the distribution of botnets that we observed in Q3 2021.

The IoT and Linux bot landscape is a wild west, as usual. We are still seeing many Gafgyt and Mirai samples trying to exploit their way onto various devices. The trend of these families borrowing the code from each other still continues, so while we sometimes see samples being worthy of being called a new strain, many samples continue to blur the line between Gafgyt and Mirai strains. We expect this trend to continue – both strains have their source code available, and the demand for DDoS does not lessen. Due to their popularity, the source code is also often used by technically less proficient adversaries, partially explaining the latter trend of code reuse.

Q3’s surprise has been the MyKings botnet which has had quite a profitable campaign. Their cryptoswapper campaign has managed to amass approximately 25 million dollars in Bitcoin, Ethereum and Dogecoin.

Changes in malware distribution methods

In Q3 2021, we saw a shift in bot and RAT distribution. Threat actors are finding new ways of abusing third party infrastructure. While we have previously seen various cloud storages (e.g. OneDrive) or Pastebin, we are also seeing more creative means such as Google’s feedproxy.google.com for C&C URLs or Discord’s CDN as a distribution channel. This makes it easier for them to avoid reputation services meant to combat malware distribution, though at the cost that their channels may get disrupted by the service provider. Since we’ve already seen communication platforms such as Discord or Telegram being also abused for exfiltration or as C&C, we can expect this trend to spread to other similar automation-friendly services.

Adolf Středa, Malware Researcher

Infrastructure as a service for malware

It seems that infrastructure as a service for malware and botnets is on the rise by using commodity routers and IoT devices. Threat actors realized that it’s far easier to misuse these devices as a proxy to hide malicious activity than crafting specific malware for such a variety of architectures and devices. It also seems that we are witnessing botnets of enslaved devices being sold as a service to various threat actors.

In Q2 and Q3, we’ve seen a new campaign dubbed Mēris. This campaign attacked Mikrotik routers, already known to be problematic since 2018, for DDoS attacks against Yandex servers. Further analysis showed that this attack had been just one of the campaigns run through the MikroTik botnet as a service providing anonymizing proxies. It turned out that the botnet consisted of approximately 200K of enslaved devices with an opened SOCKS proxy being ready for hire on darknet forums. It’s believed that this actor has been controlling this botnet since 2018. Moreover, there are ties to Glupteba and coin mining campaigns in 2018. Although most of the botnet has been taken down, the original culprit and vulnerabilities in the Mikrotik routers seem to be still open. The attack vector is notoriously well-known and is common for most of the IoT and router devices: unpatched firmware and default credentials. We’ll inevitably see more of this trend in the future.

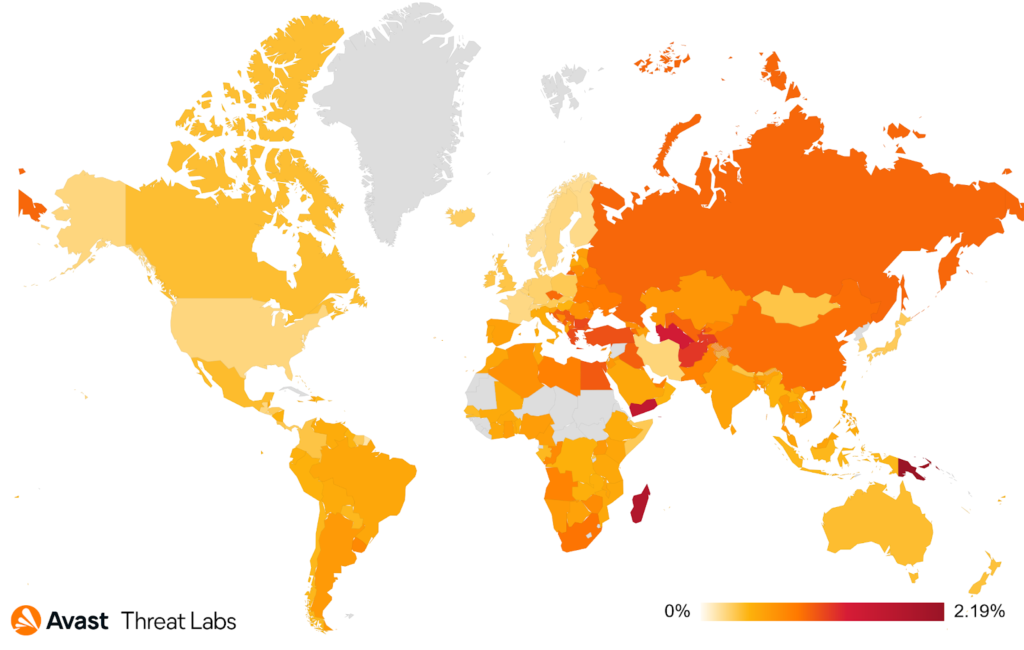

Below is a heatmap showing the prevalence of unpatched Mikrotik routers in Q3 2021.

Martin Hron, Malware Researcher

Coinminers

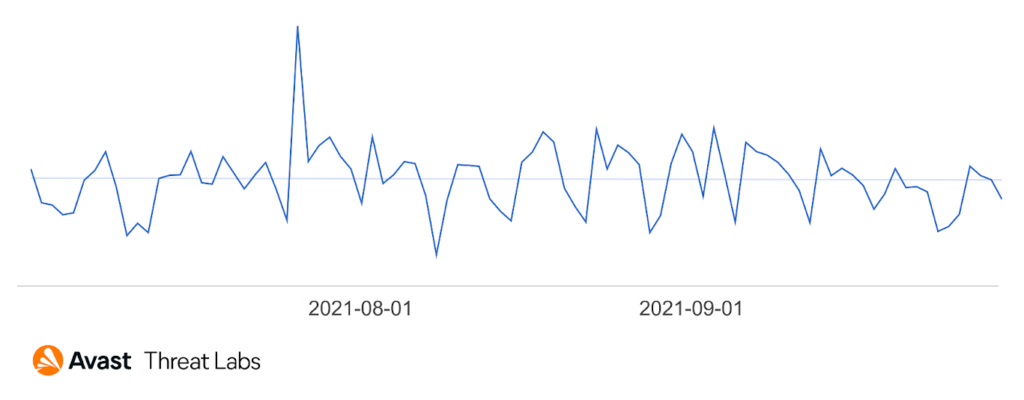

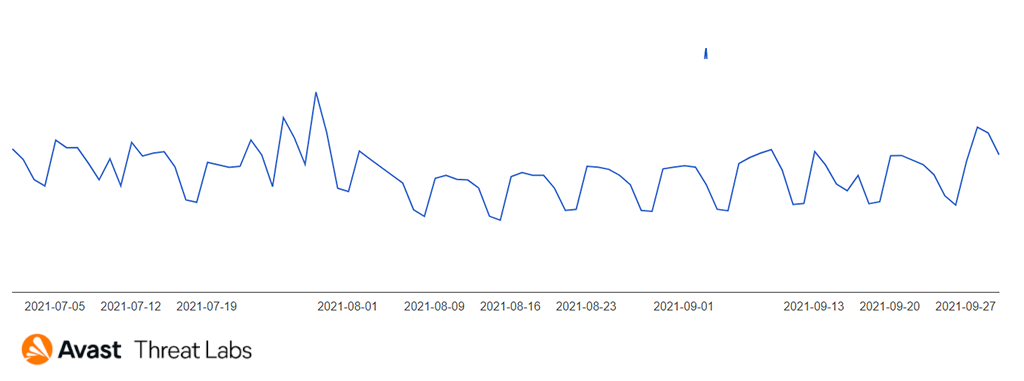

Coinminers are malware that hijacks resources of infected PCs to mine cryptocurrency and send its profit directly to the attacker while the electricity bill is left for the victim. The number of users attacked by coinminers has actually stayed steady or even lowered some in Q3 2021 compared to the beginning of the year as shown below.

It is possible that this stagnant or even lowering threat trend is due to the prices of cryptocurrencies. The prices of Bitcoin, Etherum and Monero were on the low end from the end of May until the end of July. Q3 saw a significant sell-off of Bitcoin especially in response to increased signals that the Chinese government would move to regulate cryptocurrency. As a consequence the number of coinmining attacks we saw in Q3 were low and we did not observe any new threats.

The most prevalent mining software used in coinminers was still XMRig (28%). The geological distribution of coinminers is almost the same as in Q2 as shown below.

It is hard to estimate how much the attackers obtained by mining, because they usually use untraceable cryptocurrency such as Monero. But we have some pieces of the puzzle. We were able to track some payments for Crackonosh malware. Our analysis shows that it was able to mine over $2 million USD since 2018. Crackonosh represents just about 2% of all coinminer attacks we see in our userbase. Crackonosh is packed with cracked copies of popular games, it uses Windows Safe Mode to uninstall antimalware software (note that Avast users are protected against this tactic) and then it installs XMRig to mine Monero.

Daniel Beneš, Malware Researcher

Ransomware

Q3 was a thrilling quarter from the ransomware perspective. One can almost get used to newspaper headlines about ransomware breaches and attacks on large companies on a daily basis (e.g. Olympus and Newcoop attacks by BlackMatter ransomware), but at the same time, we witnessed a huge supply chain attack not seen for a while, involvement of state leaders in addressing it and much more.

Overall, Q3 ransomware attacks were 5% higher than in Q2 and even 22% higher than in Q1 2021.

At the very beginning of Q3 (July 2), we spotted an attack of the Sodinokibi/REvil ransomware delivered via a supply chain attack on Kaseya MSP. The impact was massive – more than 1,500 businesses were targeted. Also other parts of the attack were fascinating. This particular cybercriminal group used the DLL sideloading vulnerability of Microsoft Defender for delivery of the target payload, which could have confused some security solutions. We’ve seen abuse of this particular Defender application already in May 2020. Overall, we’ve noticed and blocked this attack on more than 2.4k endpoints based on our telemetry. The story of this attack continued over Q3 with involvement of presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin resulting in ransomware operators releasing the decryption key, which helped with unlocking files of affected victims. It gave us one more clue for the attribution of the origin of this (R)evil. After the release of the decryption key, Sodinokibi went silent for almost two months – their infrastructure went down, no new variants were seen in the wild, etc. However, it was us who detected (and blocked) its latest variant on September 9. This story evolved in November, but let’s keep it for the Q4 report.

However, Sodinokibi was only one piece of the ransomware threat landscape puzzle in Q3. The top spreading strains overall were:

STOP/Djvu– often spread via infected pirated softwareWannaCry– the one and only, still spreading after four years via theEternalBlueexploitCrySiS– also spreading for a long time via hacked RDPSodinokibi/REvil- Various strains derived from open-source ransomware (

HiddenTear,Go-ransomware, etc.)

Furthermore, there were multiple active strains focused on targeted attacks on businesses, such as BlackMatter (previously DarkSide) and various ransomware strains from the Evil Corp group (e.g. Grief) and Conti.

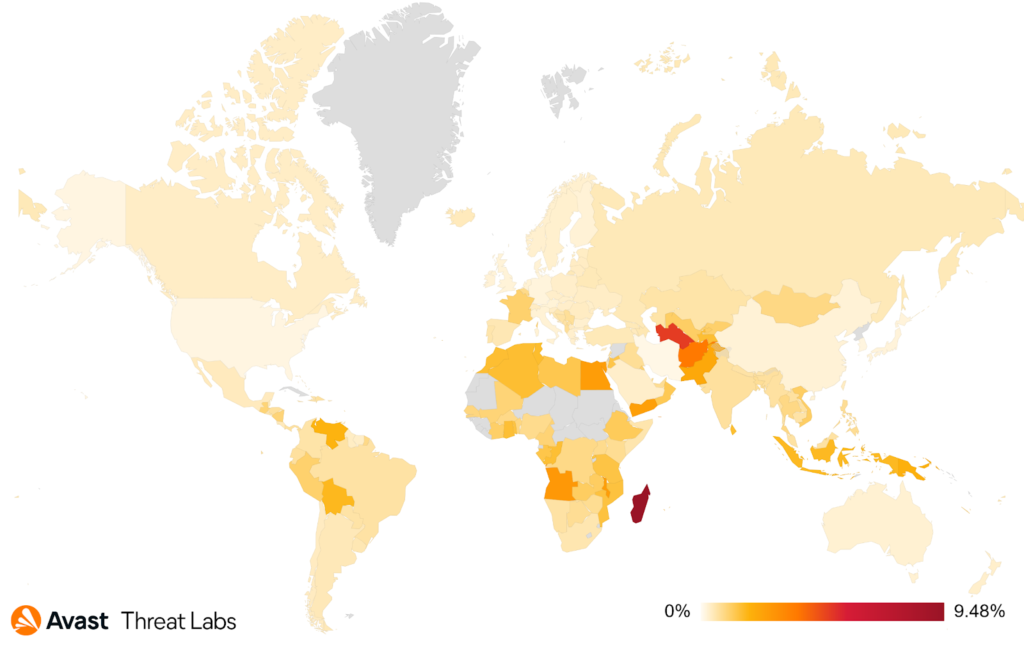

The heat map below shows the risk ratio of users protected against ransomware Q3 2021.

As shown below the distribution of ransomware attacks was very similar to previous quarters except for a 600% increase in Sweden that was primarily caused by the aforementioned Kaseya supply chain attack.

The number of protected users by ransomware attacks was highest in July, and it decreased slightly in August and September.

Jakub Křoustek, Malware Research Director

Remote Access Trojans (RATs)

Unlike ransomware, RAT campaigns are not as prevalent in newspaper headlines because of their very secretive nature. Ransomware needs to let you know that it is present on the infected system but RATs try to stay stealthy and just silently spy on their victims. The less visible they are the better for the threat actors.

In Q3, three new RAT variants were brought to our attention. Among these new RATs were FatalRAT with its anti-VM capabilities, VBA RAT which was exploiting the Internet Explorer vulnerability CVE-2021-26411, and finally a new version of Reverse RAT with build number 2.0 which added web camera photo taking, file stealing and anti-AV capabilities.

But these new Remote Access Trojans haven’t drastically changed representation of RAT type in the wild yet.

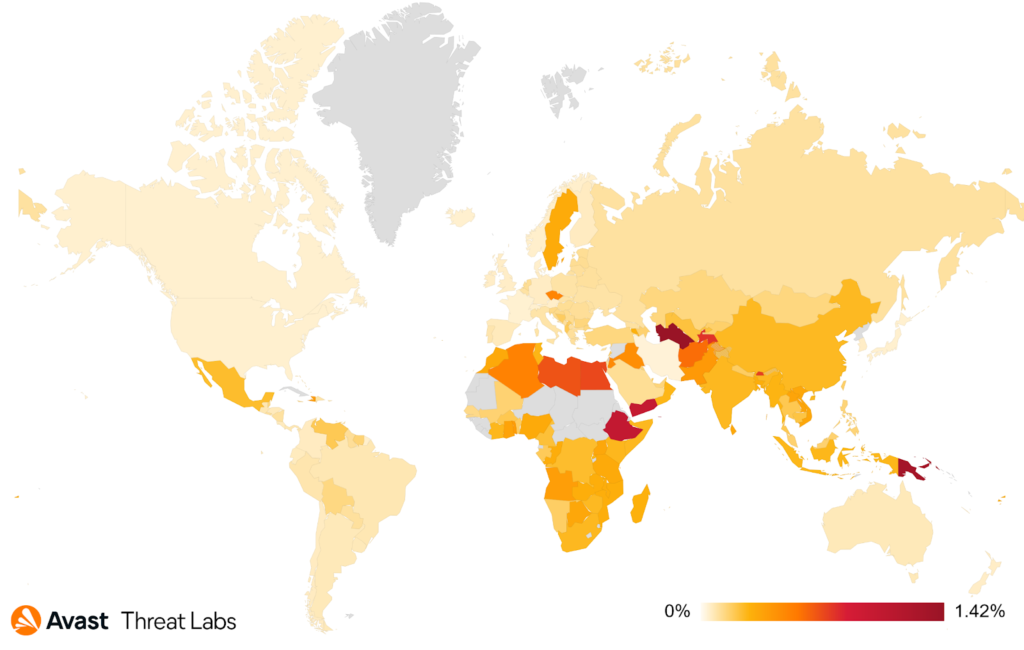

We saw an elevated risk ratio for RATs in many countries all over the world. In particular, we had to protect more users in countries such as Russia, Singapore, Bulgaria or Turkey where RAT attacks were elevated this quarter.

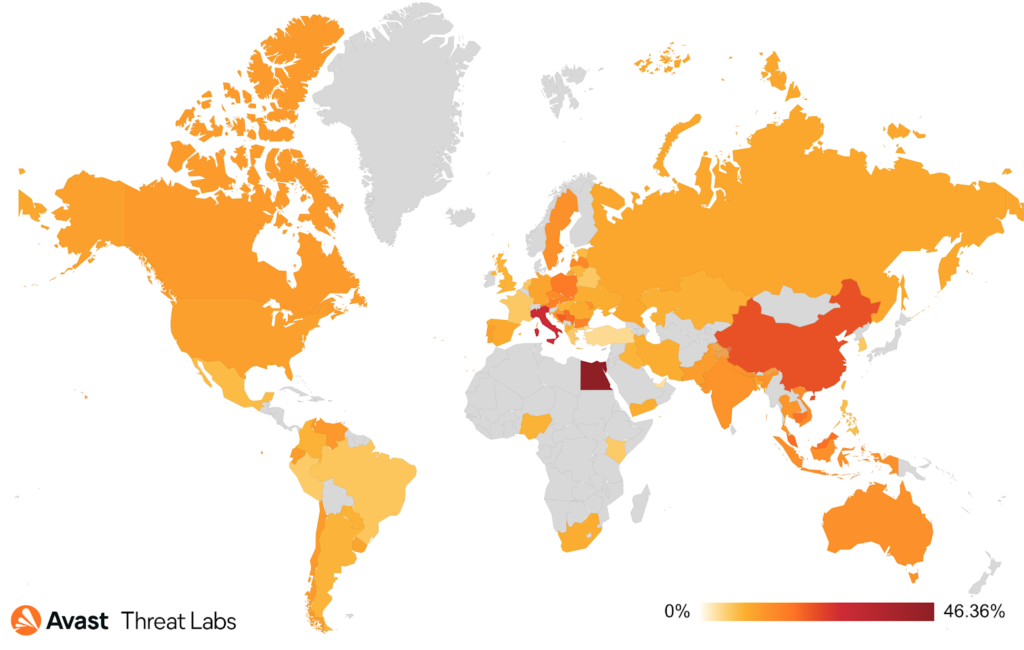

In the heat map below, we can see the risk ratio for RATs globally in Q3 2021.

Out of all users attacked by RATs in Q3, 19% were attacked by njRAT (also known as Bladabindi). njRat has been spreading since 2012 and it owes its popularity to the fact that it was open sourced a long time ago and many different variants were built on top of its source written in VB.NET. After njRAT, the most prevalent RAT strains were:

Remcos‒ 11%AsyncRat‒ 10%NanoCore‒ 9%Warzone‒ 6%QuasarRAT‒ 5%NetWire‒ 5%DarkComet‒ 4%

What made these RATs so popular and what was the reason they spread the most? The answer is simple, all of them were either open-sourced or cracked and that helped their popularity especially among less sophisticated script-kiddie attackers and among users of many hacking forums where they were often shared. njRat, Remcos, AsyncRat, NanoCore and QuasarRat were open-sourced and the rest was cracked. From this list only Warzone had a working paid subscription model from its original developer. Attackers used these RATs especially for industry espionage, credentials theft, stalking and with many infected computers, even DDOS.

Samuel Sidor, Malware Researcher

Rootkits

A rootkit is malicious software designed to give unauthorized access with the highest system privileges. Rootkits commonly provide services to other malware in the user mode. It typically includes functionality such as concealing malware processes, files and registry entries. In general, the rootkits have total control over a system they operate in the kernel layer, including modifying critical kernel structures. Rootkits are still popular techniques to hide malicious activity despite a high risk of being detected because the rootkits work in the kernel mode, and each critical bug can lead to BSoD.

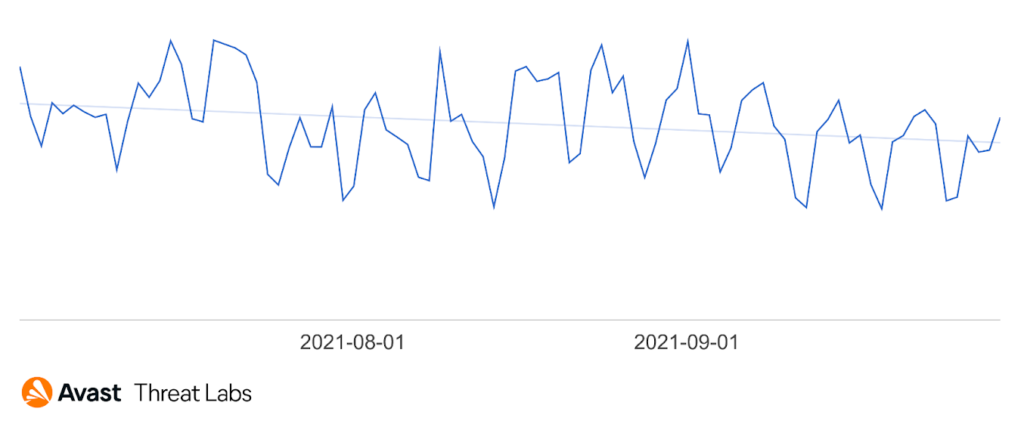

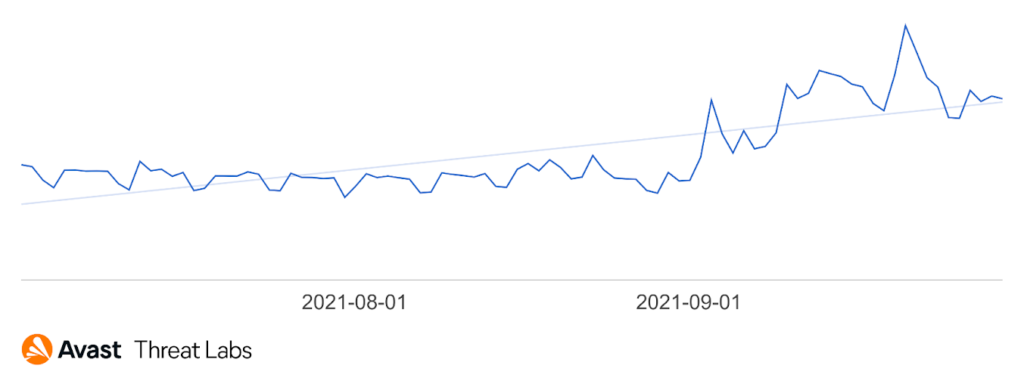

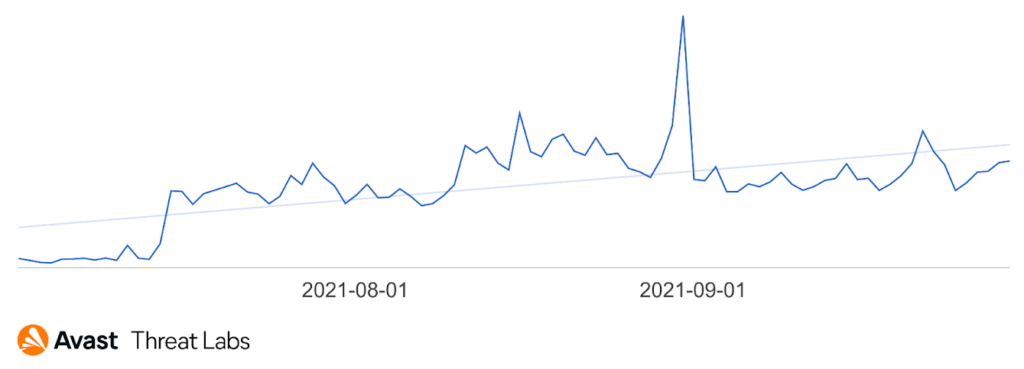

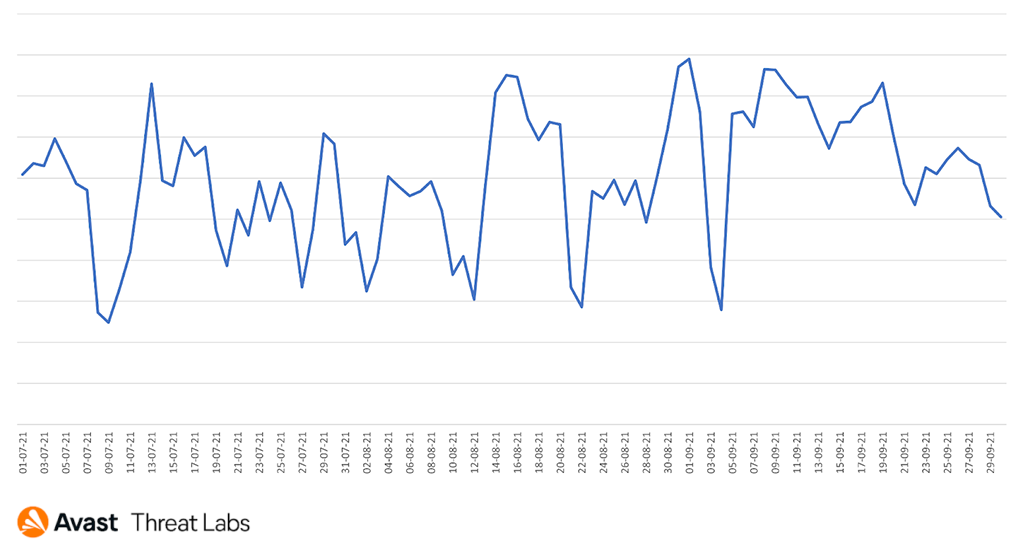

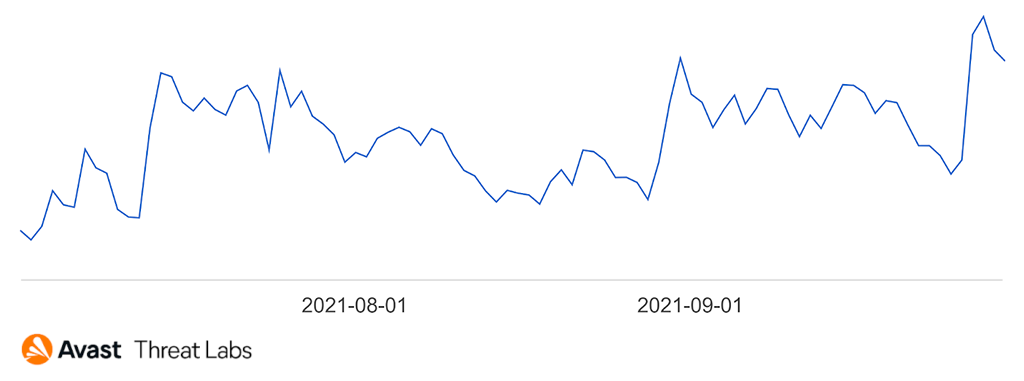

We have recorded a significant increase in rootkit activity at the end of Q3, illustrated in the chart below. While we can’t be sure what’s behind this increase, this is one of the most significant increases in activity in Q3 2021 and is worth watching. It also underscores that defenders should be aware that rootkits, which have been out of the spotlight in recent years, remain a threat and in fact are increasing once again.

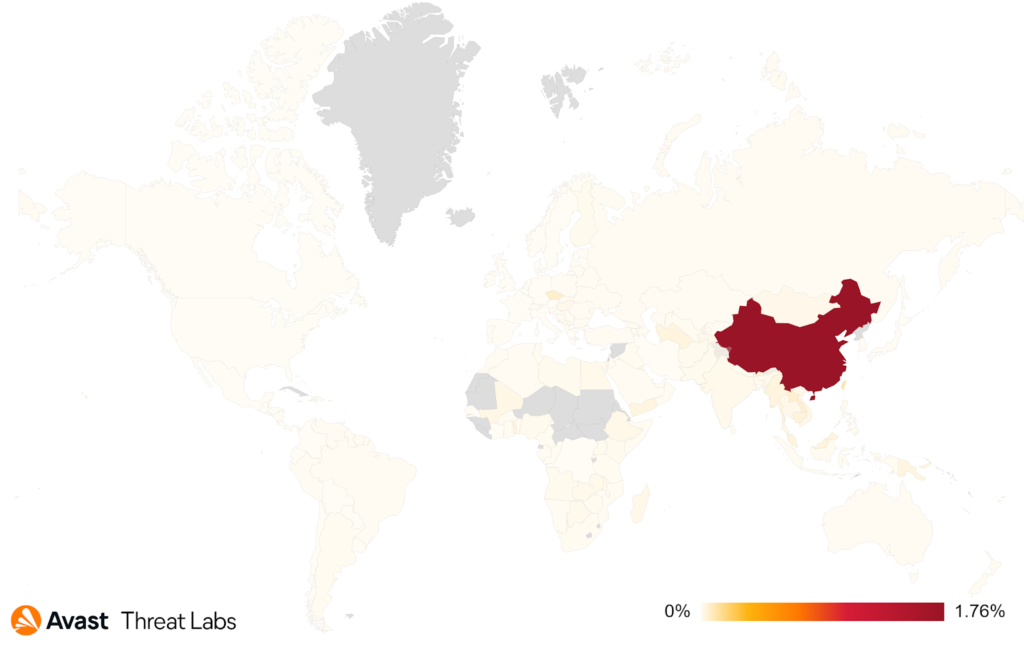

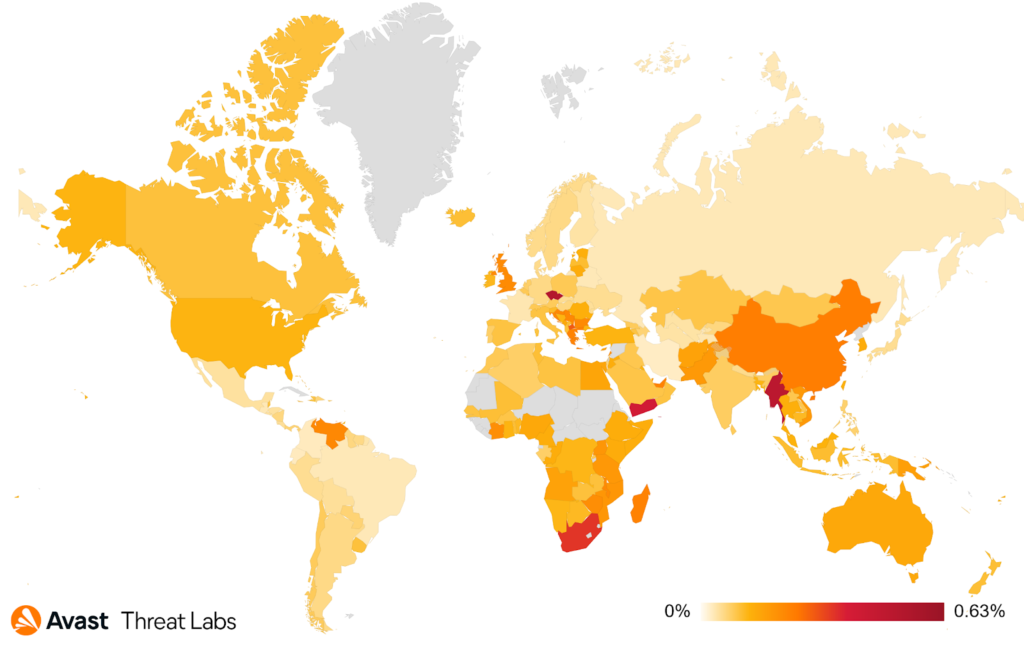

The graph below demonstrates that China and adjacent administrative areas (Macao, Taiwan, Hong Kong) are the most risk counties from the point of view of protected users in Q3 of 2021.

In Q3, we have also become interested in analyzing the code-signing of a rootkit driver, which protects the malicious activity of a complex and modularized malicious backdoor utilizing sophisticated C&C communication, self-protection mechanisms, and a wide variety of modules performing various suspicious tasks, called DirtyMoe focusing on the Monero mining.

This research has led us to the issue of signing windows drivers with revoked certificates. There have been identified 3 revoked certificates that sign the DirtyMoe rootkit and also sign other rootkits. Most users have been attacked in Russia (40%), China (20%), and Ukraine (10%).

Martin Chlumecký, Malware Researcher

Information Stealers

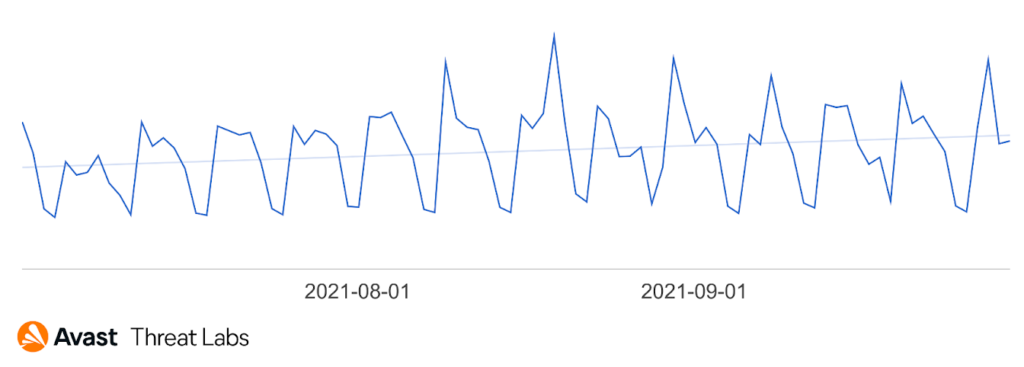

In Q3, we’ve seen a steady increase in numbers of various information stealers as can be seen on the daily spreading chart below.

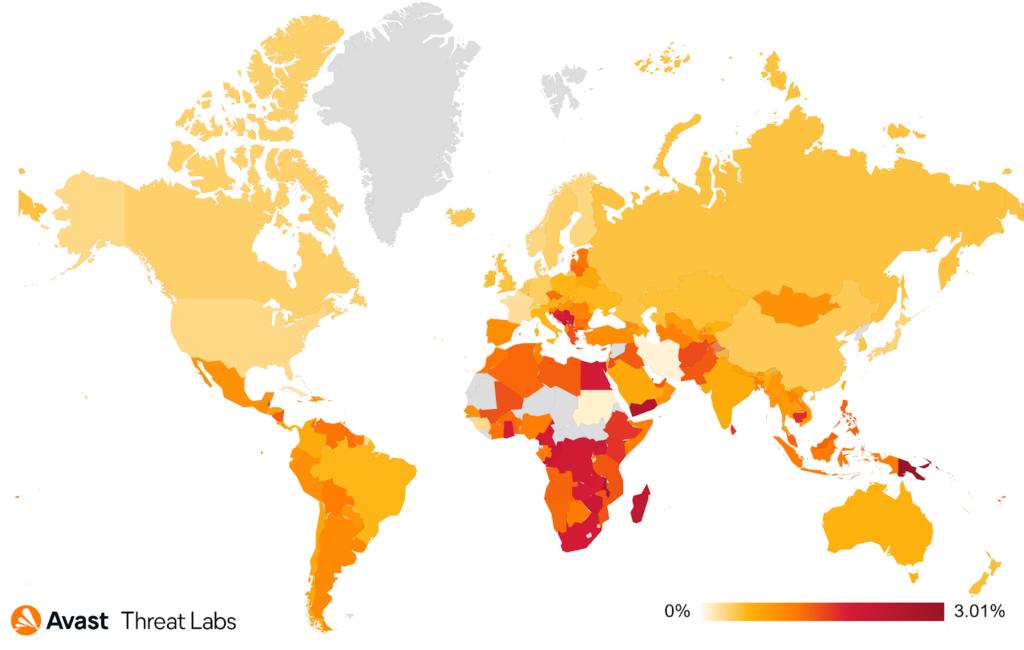

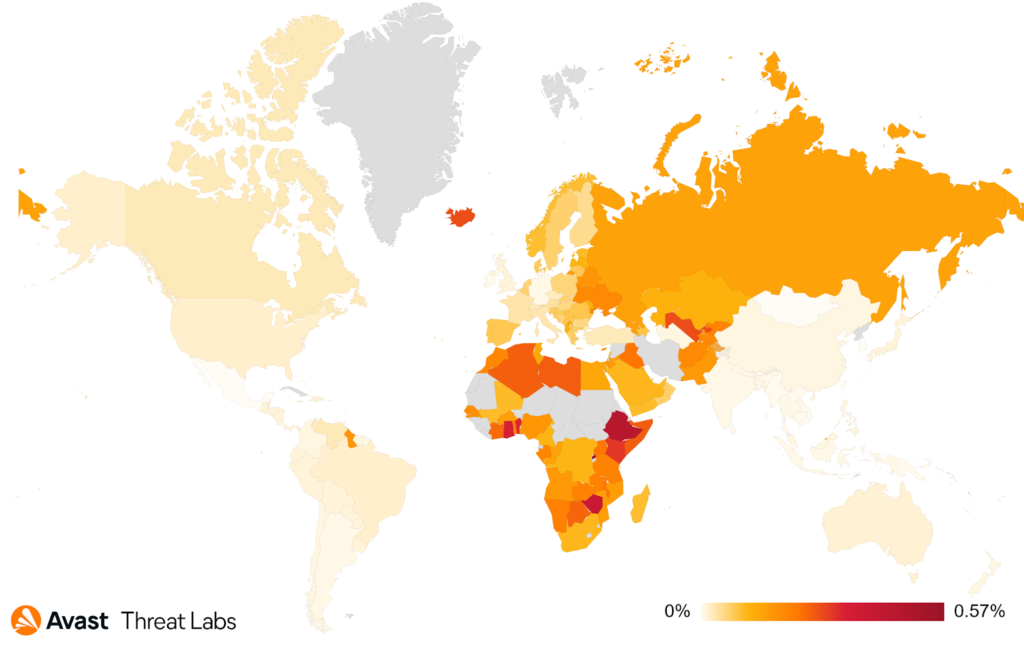

The risk ratio of this threat is globally high and similar across the majority of countries worldwide with peaks in Africa and the Middle East.

One of such stealers is a clipboard stealer, distributed by a notorious botnet called MyKings, that focuses on swapping victim’s cryptocurrency wallet addresses present in their clipboard with an attacker’s address. When the victim copies data into their clipboard, the malware tries to find a specific pattern in the content of the clipboard (such as a web page link or a format of cryptocurrency wallet) and if it is found, the content is replaced with the attackers’ information. Using this simple technique, the victim thinks for instance they pasted their friend’s cryptowallet address while the attacker changed the address in the meantime to their own, effectively redirecting the money.

MyKings also changes two kinds of links when present in the victim’s clipboard – Steam trade offer links and Yandex Disk storage links. This way, the attacker changes the Steam trade offer from the victim to himself, thus giving the trade over to the attacker who pockets the money. Furthermore, when the user wants to share a file via Yandex Disk storage cloud service, the web link is changed with a malicious one – leading the victim to download further malware because there is no reason to suspect the link is malicious when received from a friend.

Our research has shown that, since 2019, the operators behind MyKings have amassed at least $24 million USD (and likely more) as of 2021-10-05 in the Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Dogecoin cryptowallets associated with MyKings. While we can’t attribute this amount solely to MyKings, it still represents a significant sum that can be tied to MyKings activity. In addition to the aforementioned amounts, the clipboard stealer also focuses on more than 20 different cryptocurrencies, further leveraging the popularity of the cryptocurrency world. In Q3, MyKings was most active in Russia, Pakistan, and India.

Furthermore, Blustealer is a new and emerging stealer first seen at the beginning of Q3 and spiked in activities around 10-11 September. Primarily distributed through phishing emails, Blustealer is capable of stealing credentials stored in web browsers and crypto wallet data, hijacking crypto wallet addresses in clipboard, as well as uploading document files. The current version of Blustealer uses SMTP (email) and Telegram (Bot API) for data exfiltration.

Jan Rubín, Malware Researcher

Jakub Kaloč, Malware Researcher

Anh Ho, Malware Researcher

Technical support scams

Tech support scam (or TSS in short) is a big business and the people behind it use a number of techniques to try and convince you that you need their help. Most of the techniques these websites use are aimed at making your browser and system seem broken.

This topic became very popular on Youtube and TikTok as it attracted the attention of “scambaiters” – a type of vigilante who disrupts, exposes or even scams the world’s scammers.

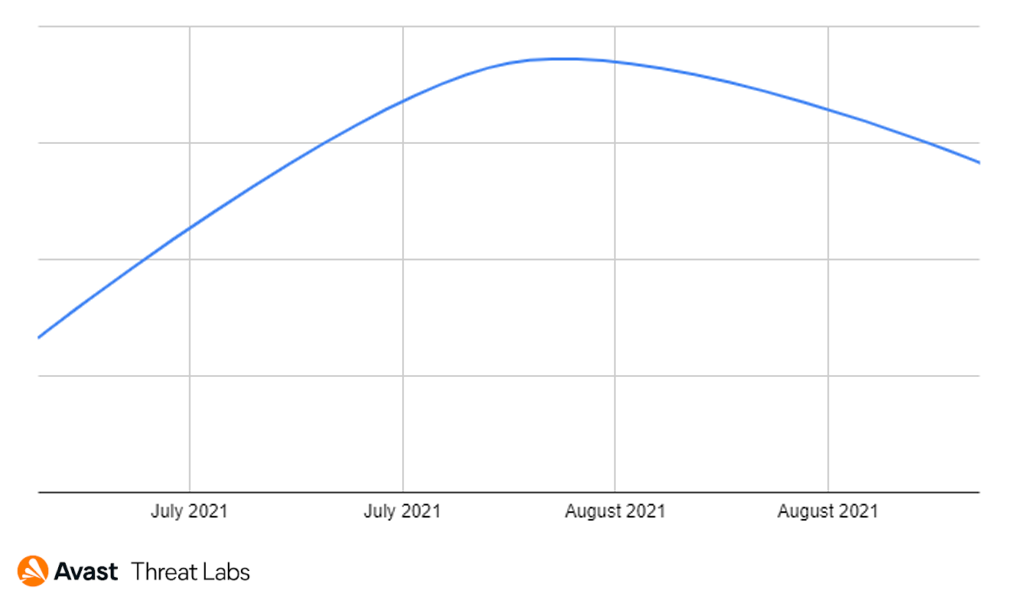

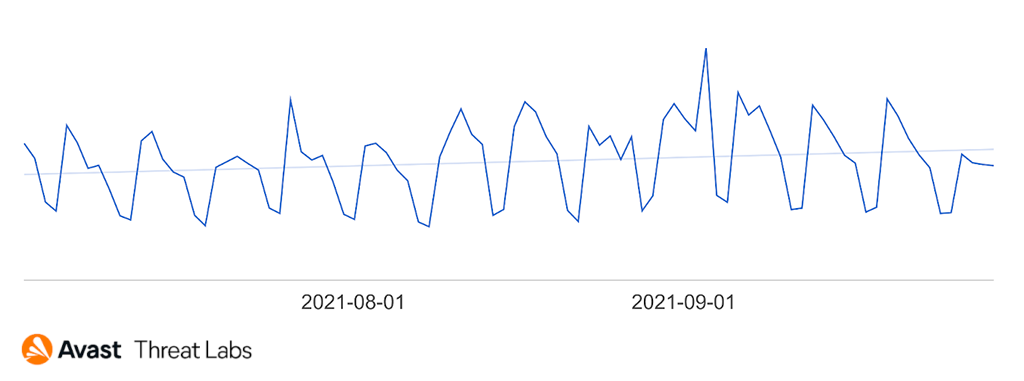

We’ve seen a growing trend of TSS attacks with its peak at the end of August as shown below..

Overall we can see the distribution of TSS attacks globally in Q3 2021 below.

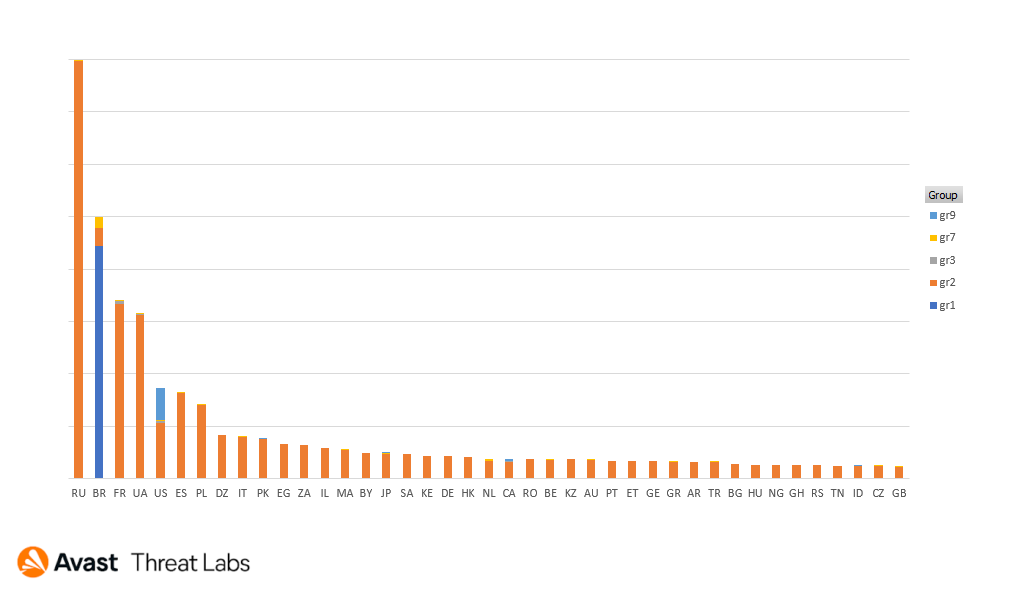

We’ve divided these fraudsters into groups according to geography and similar attack patterns. These groupings can include multiple fraud groups that use the same tool, or use similar browser locking methods. The following table represents the unique hits for each group.

The most prevalent group in Q3 2021, called GR2 by us, typically targets mostly European countries, such as Russia, France, Ukraine, or Spain. These countries also had a high TSS risk ratio overall together with Iceland, Uzbekistan, and Rwanda.

We can see how GR2 was the most active TSS group and had its peak in mid-July.

Alexej Savčin, Malware Analyst

Vulnerabilities and Exploits

Q3 has seen plenty of newly discovered vulnerabilities. Of particular interest was PrintNightmare, a vulnerability in the Windows Print Spooler, which allowed for both local privilege escalation (LPE) and remote code execution (RCE) exploits. A Proof of Concept (PoC) exploit for PrintNightmare got leaked early on, which resulted in us seeing a lot of exploitation attempts by various threat actors. PrintNightmare was even integrated into exploit kits such as PurpleFox, Magnitude, and Underminer.

Another vulnerability worth mentioning is CVE-2021-40444. This vulnerability can either be used to create malicious Microsoft Office documents (which can execute malicious code even without the need to enable macros) or it can be exploited directly against Internet Explorer. We have seen both exploitation methods used in-the-wild, with a lot of activity detected shortly after the vulnerability became public in September 2021. One of the first exploit attempts we detected was against an undisclosed military target, which proves yet again that advanced attackers waste no time weaponizing promising vulnerabilities once they become public.

We’ve also been tracking exploit kit activity throughout Q3. The most active exploit kit was PurpleFox, against which we protected over 6k users per day on average. Rig and Magnitude were also prevalent throughout the whole quarter. The Underminer exploit kit woke up after a long period of inactivity and started sporadically serving HiddenBee and Amadey. Even though it might seem that exploit kits are becoming a thing of the past, we’ve witnessed that some exploit kits (especially PurpleFox and Magnitude) are being very actively developed, regularly receiving new features and exploitation capabilities. We’ve even devoted a whole blog post to the recent updates in Magnitude. Since that blog post, Magnitude continued to innovate and most interestingly was even testing exploits against Chromium-based browsers. We’ll see if this is the beginning of a new trend or just a failed experiment.

Overall, Avast users from Singapore, Czechia, Myanmar, Hong Kong and Yemen had the highest risk ratio for exploits, as can be seen on the following map.

The risk ratio for exploits was growing in Q3 with its peak in September.

Michal Salát, Threat Intelligence Director

Jan Vojtěšek, Malware Researcher

Web skimming

Ecommerce websites are much more popular than they used to be, people tend to shop online more and more often. This led to the growth of an attack called web skimming.

Web skimming is a type of attack on ecommerce websites in which an attacker inserts malicious code into a legitimate website. The purpose of the malicious code is to steal payment details on the client side at the moment the customer fills in their details in the payment form. These payment details are usually sent to the attacker’s server. To make the data flow to a third-party resource less visible, fraudsters often register domains resembling the names of popular web services like google-analytics, mastercard, paypal and others.

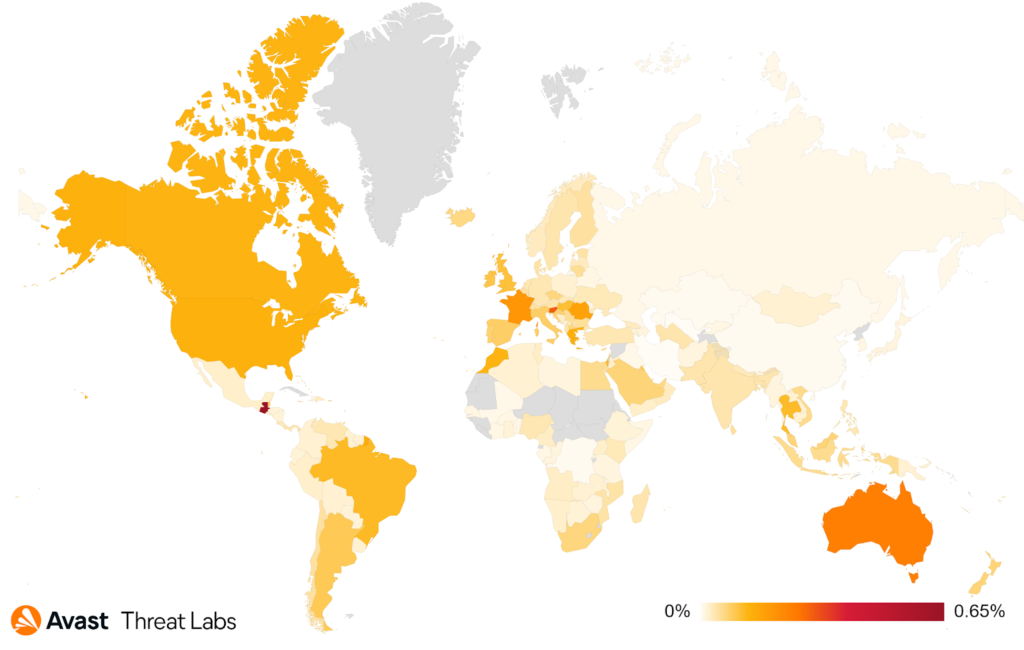

The map below shows that users from Australia, the United States, Canada, Brazil and Argentina were most at risk in Q3. Of the smaller countries, we can see Guatemala and Slovenia at the top. The high risk ratio in Guatemala was caused by an infected eshop elduendemall[.]com.

Top two malicious domains used by attackers were webadstracker[.]com and ganalitics[.]com. Webadstracker[.]com was blocked by Avast from 2021-03-04 and was active from then for the whole Q3. It indicates that unlike phishing sites, which are active usually for a couple of days, web skimming domains can be active much longer. Webadstracker[.]com is hosted on Flowspec, which is known as one of the bulletproof hosting providers. From all web skimming incidents we observed, 8.6% were on this domain. With this domain, we can link other domains on the same IP, which was also used for web skimming attacks in Q3:

webscriptcdn[.]comcdncontainer[.]comcdnforplugins[.]comshoppersbaycdn[.]comhottrackcdn[.]comsecure4d[.]net

We were able to link this IP (176.121.14.143) with 75 infected eshops. Lfg[.]com[.]br was the top ecommerce website infected with webadstracker[.]com was in Q3.

Pavlína Kopecká, Malware Analyst

Mobile

Open Firebase instances

Firebase is Google’s mobile and web app development platform. Developers can use Firebase to facilitate developing mobile and web apps, especially for the Android mobile platform. In our study we discovered that more than 10% of about 180,000 tested Firebase instances, used by Android apps, were open. The reason is a misconfiguration, made by application developers. Some of these DBs exposed sensitive data, including plaintext passwords, chat messages etc. These open instances pose a significant risk of users’ data leakage. Unfortunately, ordinary users can’t check if DB used by an application is misconfigured, moreover it can become open at any moment.

Vladimir Martyanov, Malware Researcher

Adware

Adware continues to be a dominant threat on Android. This category may take various forms – from traditional aggressive advertising on either legitimate or even fake applications to completely fake applications that, while installed with an original purpose of stopping adware, end up doing exactly the opposite and bombard the user with out-of-context ads (for example FakeAdBlocker).

The degree to which the aggressive advertisement is shown to the user – either in app or out-of-context very negatively affects the user’s experience, not to mention that in the case of out-of-context ads the user has a very difficult time of actually locating the source of such spam.

A special category in this regard is the so called Fleeceware, which we have been observing both on iOS and Android already for quite some time, this type of threat is still present in Q3 in the official marketplaces and users should be aware of such techniques so that they can actively avoid falling for it.

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Bankers – FluBot

We have seen a steady increase in the number of mobile banking threats for a while now, but none more than in Q3 2021. This can be best evidenced on a strain called FluBot – while this strain has been active since Q1/Q2, we’ve seen it make a couple of rounds since then. By Q3 it became an established threat in the Android banking threat landscape.

Its advanced and highly sophisticated spreading mechanisms – using SMS messages typically posing as delivery services to lure the victims into downloading a “tracking app” for a parcel they recently missed or should be expecting – as well as the relentless campaigns account for a successful strain in the field. But even these phishing SMS messages (aka. smishing) have evolved and especially in Q3 we have seen novel scenarios in spreading this malware. One example is posing as voicemail recorders. Another is fake claims of leaked personal photos. The most extreme of these variants would then even lure the victim to a fake page that would claim the victim has already been infected by FluBot when they probably weren’t yet and trick them into installing a “cure” for the “infection”. This “cure” would in fact be the FluBot malware itself.

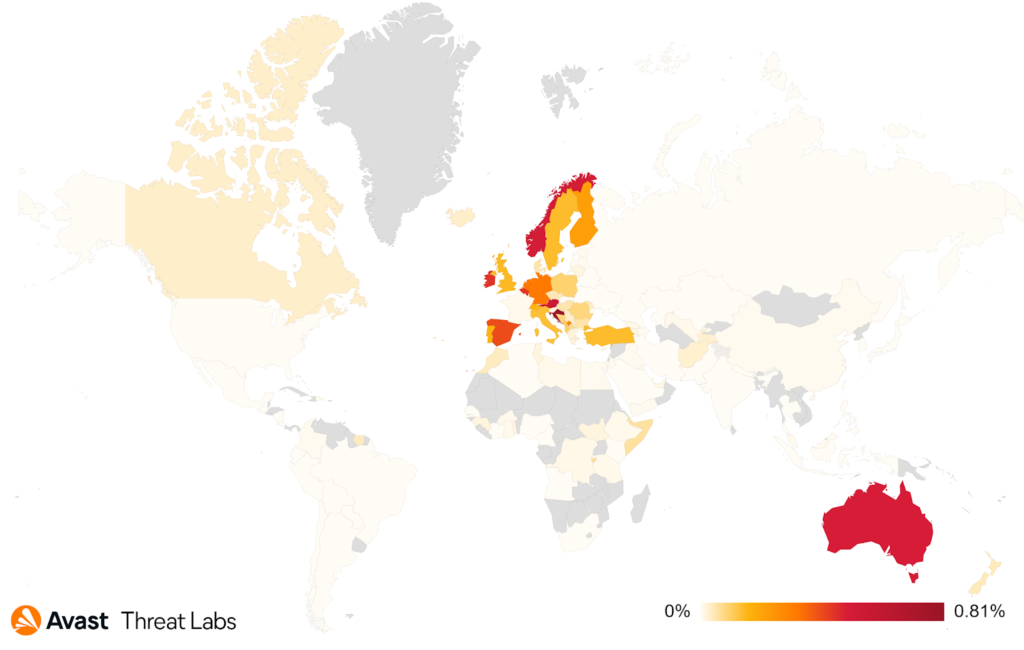

We have seen a steady expansion of the scope where FluBot operated throughout Q2 and mainly Q3, where initially it was targeting Europe – Spain, Italy, Germany, later spreading throughout the rest of Europe, but it didn’t end there. In Q3 we’ve seen advisories being posted in many other countries, including countries like Australia and New Zealand. This threat affects only Android devices – iOS users may still occasionally receive the phishing SMS messages, but the malware would not be able to infect the device.

The heat map below shows the spread of Flubot in Q3 2021 and the graph shows the increase in Flubot infections in that same time period.

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Pegasus

Perhaps the most discussed mobile threat in Q3 was the infamous Pegasus spyware. Developed by Israeli’s NSO Group this threat targeted primarily iOS device users with known Android variants as well. Due to the usage of zero-click vulnerabilities in the iMessage application the attackers were able to infect the device without any user interaction necessary. This makes it a particularly tricky and sophisticated threat to deal with. Fortunately for the majority of the users this type of attack is unlikely to be used on a mass scale, but rather in a highly targeted manner against high profile or high value targets

Acting as a full blown spyware suite, Pegasus is capable of tracking location, calls, messages and many other personal data. Pegasus as a strain is not exactly new, its roots go deep into history as far back as at least 2016. The threat as well as its distribution methods have changed significantly since the early days however. For a successful stealthy distribution of this threat the malicious actors needed to keep finding vulnerabilities in the ever updating OS or default apps that could be used as a way to infect the device – ranging from remote jailbreaks to the latest versions utilizing zero-click exploits.

Best protection against this type of threat is to keep your mobile device’s operating system updated to the latest version and have all the latest security updates installed.

Ondřej David, Malware Analysis Team Lead

Acknowledgements / Credits

Malware researchers

- Adolf Středa

- Alexej Savčin

- Anh Ho

- Daniel Beneš

- David Jursa

- Igor Morgenstern

- Jakub Kaloč

- Jakub Křoustek

- Jan Rubín

- Jan Vojtěšek

- Luigino Camastra

- Martin Chlumecký

- Martin Hron

- Michal Salát

- Ondřej David

- Pavlína Kopecká

- Samuel Sidor

- Vladimir Martyanov

Data analysts

- Lukáš Zobal

- Pavol Plaskoň

- Petr Zemek

Communications

- Christopher Budd

- Marina Ziegler