Reusing binary code from malware is one of my favorite topics. Binary re-engineering and being able to bend compiled code to your will is really just an amazing skill. There is also something poetic about taking malware decryption routines and making them serve you.

Over the years this topic has come up again and again. Previous articles have included emit based rips [1], exe to dll conversion [2], emulator based approaches [3], and even converting malware into an IPC based decoder service [4].

The above are all native code manipulations which makes them something you can work with directly. Easy to disassemble, easy to debug, easy to patch. (Easy being a relative term of course :))

Lately I have been working on VB6 P-Code, and developing a P-Code debugger. One goal I had was to find a way to call a P-Code function, ripped from a malware, with my own arguments. It is very powerful to be able to harness existing code without having to recreate it (including all of its nuances.)

Is this even possible with P-Code? As it turns out, it is possible, and I am going to show you how.

The distilled knowledge below is small slice of what was unraveled during an 8 month research project into the VB6 runtime and P-code instruction set.

This paper includes 11 code samples which showcase a wide variety of scenarios utilizing this technique [5].

Note on offsets

In several places throughout this paper there may be VB runtime offsets presented. All offsets are to a reference copy with md5: EEBEB73979D0AD3C74B248EBF1B6E770 [6]. Microsoft was kind enough to publish debug symbols for this build including those for the P-Code engine handlers.

Barriers to entry

The VB6 runtime was designed to load executables, dlls, and ocx controls in an undocumented format. This format contains many complex interlinked structures that layout embedded forms, class structures, dependencies etc. During startup the runtime itself also requires certain initialization steps to occur as it prepares itself for use.

If we wish to execute P-Code buffers out of the context of a VB6 host executable there are several hurdles we must overcome:

VB Runtime Initialization

Standard runtime initialization for executables takes place through the ThunRTMain export. This is the primary entry point for loading a VB6 executable. This function takes 1 argument that is the address of the top level VB Header structure. This structure contains the full complex hierarchy of everything else within.

While we can utilize this path for our needs, there are easier ways to go about it. Starting from ThunRTMain can also create some problems on process termination so we will avoid it.

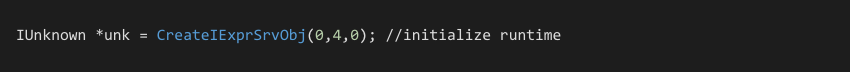

In 2003 when exploring VB6’s ability to generate standard dlls I found a second path to runtime initialization through the CreateIExprSrvObj export.

This export is simple to call and automatically performs the majority of runtime initialization. Some TLS structure fields however are left out. In testing, most things operate fine. The only errors discovered occur when trying to use native VB file commands, MsgBox or the built in App object.

With a little extra leg work it has been found that the TLS structures can be manually completed to regain access to most of this native functionality.

Finally if the P-Code buffer creates COM objects, a manual call to CoInitilize must also be performed.

Replicating basic object structures

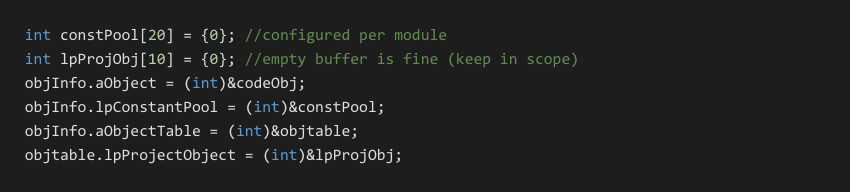

Once CreateIExprSrvObj has been executed, we can call into P-Code streams as many times as we want from our loader code. Structure initialization is minimal and only requires the following fields:

If the P-Code routines utilize global variables then the codeObj.aModulePublic field will also have to be set to a writable block of memory. This has been demonstrated in the globalVar and complex_globals examples. We can even pre-initialize these variables here if we desire.

In addition to filling out these primary structures, we also have to recreate the constant pool as expected by the specific P-Code. Finally we must also update a structure field in the P-Code to point to our current object Info structure.

While this may sound complex, there is a generator utility which automatically does all of the work for you in the majority of cases. A more detailed explanation of the following code will be presented in later sections.

Finding an entrypoint to transition into P-Code execution

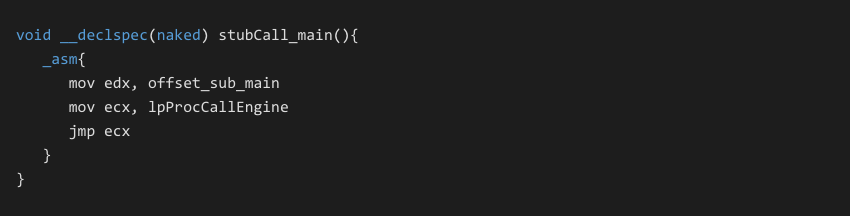

Execution of the VB6 P-Code occurs by calling the ProcCallEngine export of the VB runtime. The stub below is the same mechanism used internally by VB compiled applications to transfer execution between sub functions.

The offset_sub_main argument moved into EDX is the address of the target P-Code functions trailing structure that defines attributes of the function. We will discuss this structure in the following sections.

The asm stub above shows the default scenario of calling a P-Code function with no arguments. A video showing this running in a debugger is available [7].

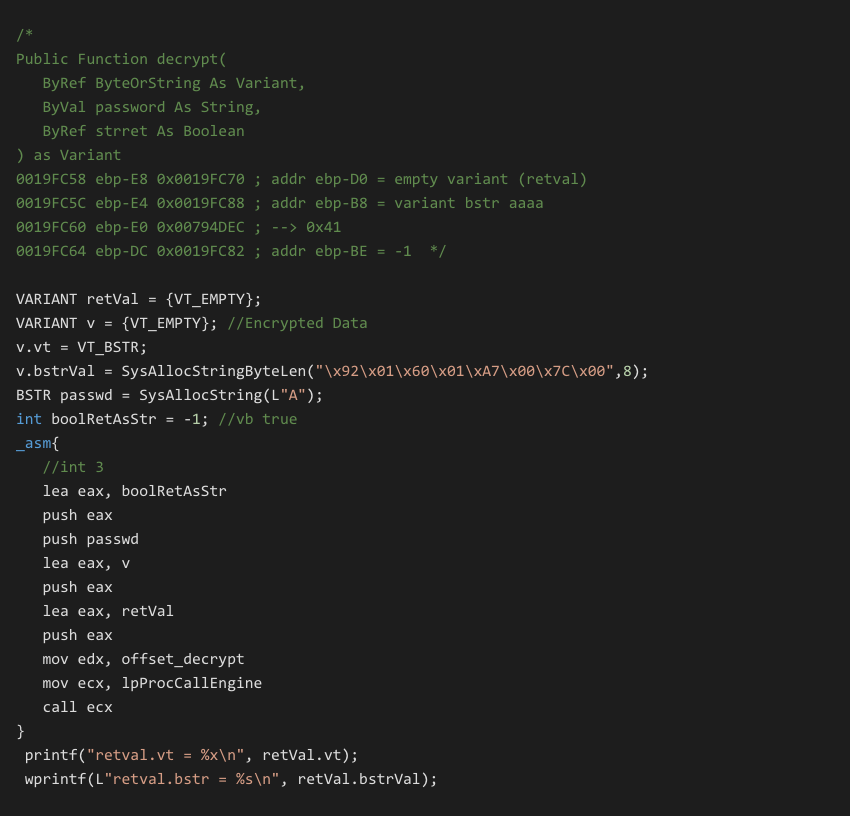

In the decrypt_test example we explore how to call a ripped function with a complex prototype and a Variant return value. This example demonstrates reusing an extracted P-Code decoder from a malware executable. Here we can call the extracted P-Code function passing it our own data:

Understanding P-Code function layout

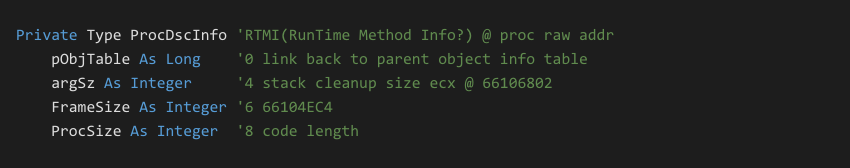

P-Code functions in compiled executables are linked by a structure that trails the actual byte code. This structure is called RTMI in the VB runtime symbols and the reversing community has taken to it as ProcDscInfo. A partial excerpt of this structure is shown below:

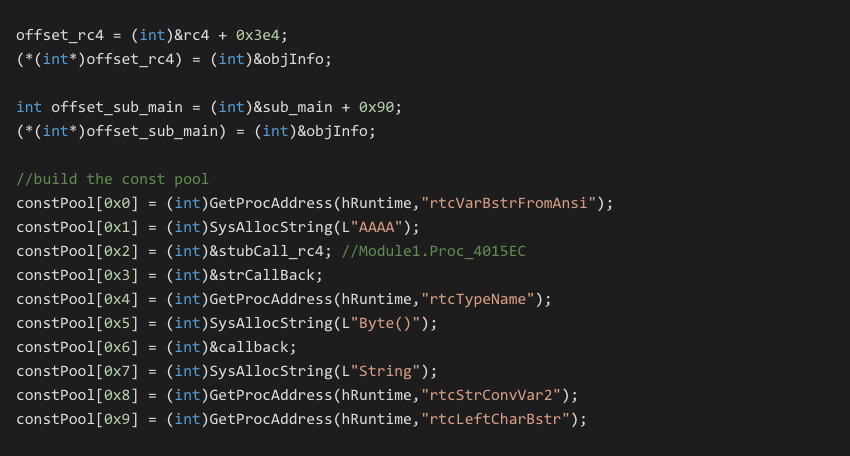

When we rip a P-Code function from a compiled binary, we must also extract the configured RTMI structure. ProcCallEngine requires this information in order to run a P-Code routine successfully.

When we relocate the P-Code block outside of the target binary, we must also update the link to our new object Info table.

This is what is being set in the generated code:

Here the rc4 buffer contains the entire ripped function, starting with the P-Code and then followed by the RTMI structure which starts at offset 0x3e4. We then patch in the address of our manually filled out object Info into the RTMI.pObjTable field. Once this is complete, the P-Code is ready for execution.

Code Generation

When developing a method such as this, we must start with known quantities. For our purposes we are writing our own test code which is done normally in the VB6 Integrated Development Environment. This code is then extracted using a utility which generates the C or VB6 source necessary to execute it independently.

The generator tool we are using in this paper is the free VBDec [8] P-Code debugger.

While exploring this technique, the sample code has been optimized to follow several conventions for clarity. For this research all code samples were ripped from functions in a single module. This design was chosen so that all sub function access occurs through the ImpAdCall* opcodes which draw directly against function pointers in the const pool.

Code taken from instanced form or class compilation units would require support to replicate VTable layouts for the *Vcall opcodes. While this can be done I will leave that as future work for now.

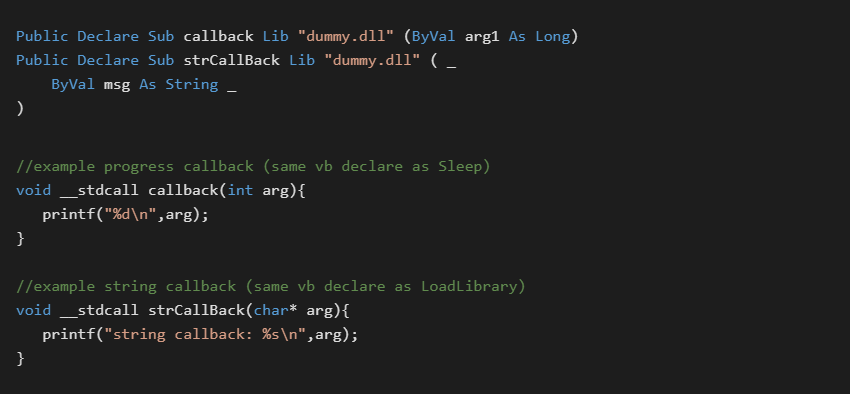

Samples are available that make extensive use of callbacks to integrate tightly with the host code. This is useful for integrating debug output through the C host in a simple manner.

Callbacks are accessed through the standard VB API Declare syntax which is a core part of the language and is well documented. Below are examples of sending both numeric and string debug info from the P-Code to the host.

Giving VB direct access to the host functions, is as simple as setting their address in the corresponding constant pool slot.

Ripping functions with VBDec is simple. Simply right click on the function in the left hand treeview and choose the Rip menu option. VBDec will generate all of the embedding data for you. Multiple functions can be ripped at once by right clicking on the top level module name.

A corresponding const pool will also be auto-generated along with stubs to update the object Info pointers and asm stubs to call interlinked sub functions.

Once extraction/generation is complete it is left up to the developer to integrate the data into one of the sample frameworks provided.

A spectrum of samples are provided ranging from very simple, to quite complex. Samples include:

| Sample | Description |

firstTest | simple addition test |

globalVar | global variables test |

structs | passing structs from C to P-Ccode |

two_funcs | interlink two P-Code functions |

ConstPool | test decoding a binary const pool entry |

lateBinding | late bind sapi voice example |

earlyBinding | early bind sapi voice example |

decrypt_test | P-Code decryptor w/ complex prototype |

Variant Data | C host returns variant types from callback to P-Code. |

benchmark | RC4 benchmarking apps in C/P-Code code and straight C |

Understanding the Const Pool

Each compilation unit such as a module, class, form etc gets its own constant pool which is shared for all of the functions in that file. Pool entries are built up on demand as the file is processed by the compiler from top to bottom.

The constant pool can contain several types of entries such as:

- string values (

BSTRsspecifically) - VB method native call stubs

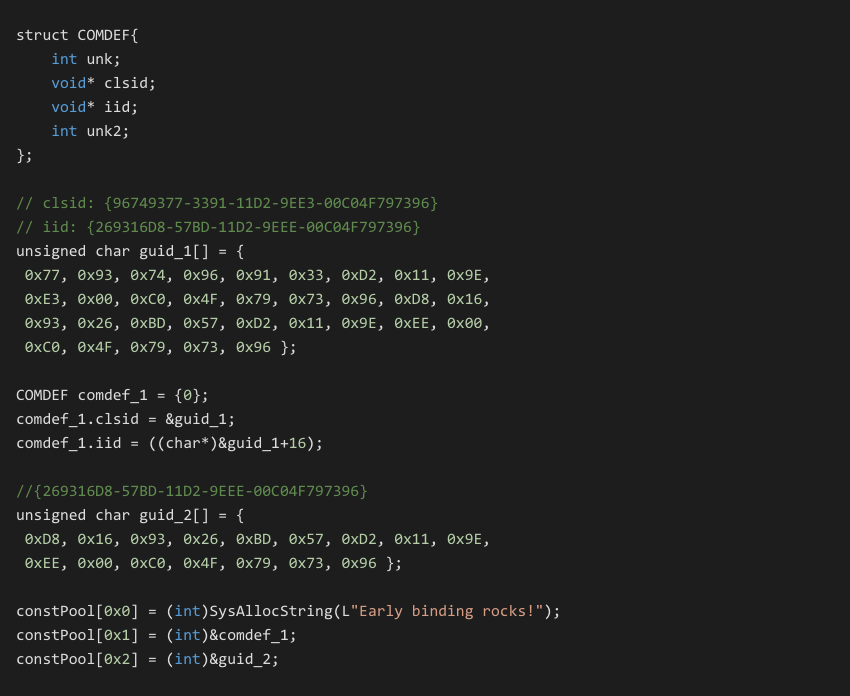

- API import native call stubs

COM GUIDsCOM CLSID / IIDpairs held inCOMDEFstructuresCodeObjectbase offsets (not applicable to our work here)- internal runtime

COMobjects filled out at startup (not supported)

VBDec is capable of automatically deciphering these entries and figuring out what they represent. Once the correct type has been determined, it can generate the C or VB source necessary to fill out the const pool in the host code. The constant pool viewer form allows you to manually view these entries.

In testing it has been performing extremely well outputting complete const pools which require little to no modification.

For callback integration with the host, if you use “dummy” as the dll name, it will automatically be assumed as a host callback. Otherwise it will be translated literally as a LoadLibrary/GetProcAddress call.

Some const pool entries may show up as Unknown. When you click on a specific entry the raw data at that offset will be loaded into the lower textbox. If this data shows all 00 00 00 00’s then this is a reference to an internal VB runtime COM object that would normally be set to a live instance at initialization.

This has been seen when using the App Object. Normally this would be set @6601802F inside _TipRegAppObject function of the runtime on initialization. These types of entries are not currently supported using this technique (and would not make sense in our context anyways.)

Interlinked sub functions are supported. A corresponding native stub will be generated along with an entry in the const pool for it.

Early binding and late binding to COM objects is also supported. Late binding is done entirely through strings in the const pool. For early binding you will seen a COMDEF structure and CLSID / IID data automatically generated.

The following is taken from the early binding sample which loads the Sapi.SpVoice COM object.

Generation of this code is generally automatic by VBDec but there may be times where the tool can not automatically detect which kind of const pool entry is being specified. In these cases you may have to manually explore the const pool and extract the data yourself.

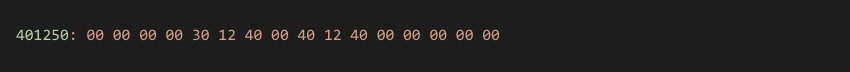

In the above scenario the file data at the const pool address may look similar to the following:

If we visualize this as a COMDEF structure we can see the values 0, 0x401230, 0x401240, 0. Looking at the file offsets for these virtual addresses we find the GUIDs given above.

String entries are held as BSTRs, which is a length prefixed unicode string. Since we are in complete control of the const pool, and BSTRs can encapsulate binary data. It is possible to include encrypted strings directly in the const pool using SysAllocStringByteLen. The binary_ConstPool* samples demonstrate this technique. You can also dynamically swap out const pool entries to change functionality as the P-Code runs. An example of this is found in the early bind sample.

Note: It is important to use the SysAlloc* string functions to get real BSTR’s for const pool entries. As the strings get used by the runtime, it may try to realloc or release them.

Extended TLS Initialization

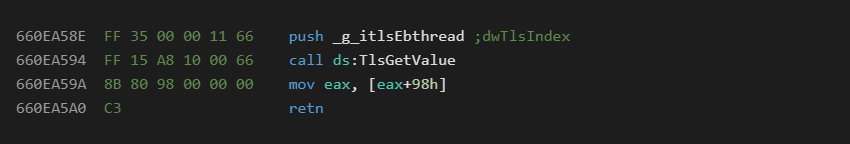

The VB6 runtime stores several key structures in Thread Local Storage (TLS). Several functions of the runtime require these structures to be initialized. These structures are critical for VB error handling routines and can also come into play for file access functions.

Below is the code for the rtcGetErl export. This function retrieves the user specified error line number associated with the last exception that occurred.

From this snippet of code we can see that the runtime stores the TLS slot value at offset 66110000. Once the actual memory address is retrieved with TlsGetValue The structure field 0x98 is then returned as the stored last error line number. In this manner we can begin to understand the meaning of the various structure offsets.

Even without a full analysis of the complete 0xA8 byte structure we can compare the values seen between a fully initialized process with those initialized through the CreateIExprSrvObj export.

Once diffed 2 main empty slots are observed which normally point to other allocations.

- field

0x18– normally set@ 66015B25inEbSetContextWorkerThread - field

0x48– normally set@ 66018081inRegAppObjectOfProject

Field 0x48 is used for access to the internal VB App. COM object. This object does not make sense to use in our scenario and does not trigger any exceptions if left blank. If we had to replicate the COM object for compatibility with existing code we could however insert a dummy object.

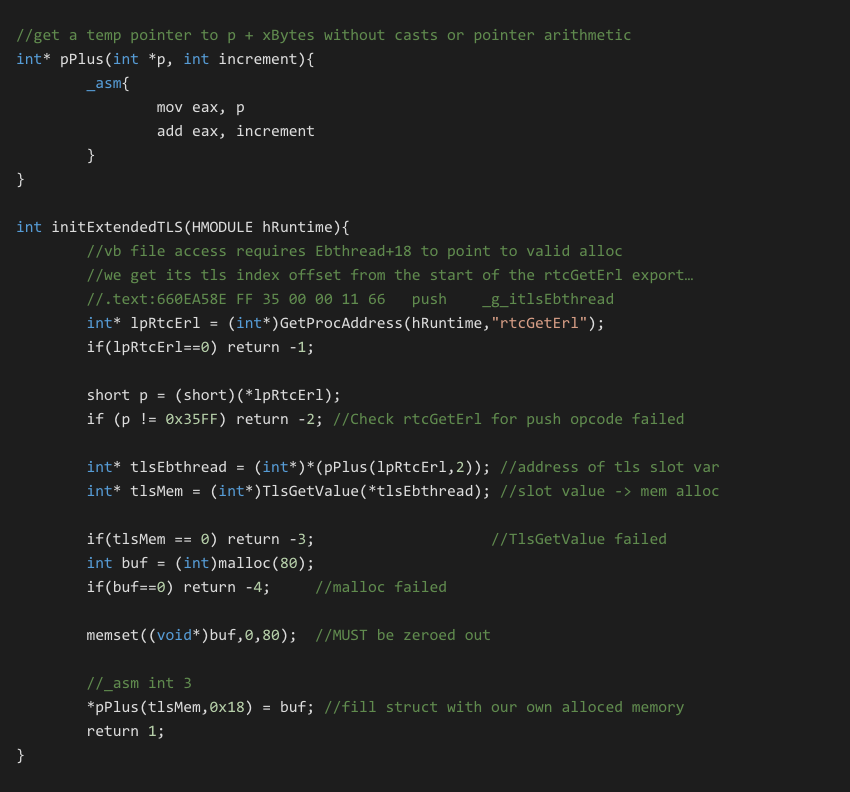

The allocation at offset 0x18 is only required if we wish to use built in VB file operation commands or the MsgBox function.

If demanded for compatibility with ripped code, It was interesting to see if a manual allocation would allow the runtime to operate properly.

The following code was created to dynamically lookup the TLS slot value, retrieve the tlsEbthread memory offset and then manually link in a new allocation to the missing 0x18 field.

Once the above code was integrated full access was restored to the native VB file access functions. Again this extended initialization is not always required.

Debugging integration’s

When testing this technique it is best to start with your own code that you control. This way you can get familiar with it and develop a feel for working with (and recognizing) the different function prototypes.

The first step is to write and debug your VB6 code as normal in the VB6 IDE. In preparation for running as a byte buffer, you can then pepper the VB code with progress callbacks to API Declare routines which normally access C dll exports.. You don’t actually have to write the dll, but you can. The calls are identical when hosted internally from a native C loader (or even a VB hosted Addressof callback routine).

If you are calling into a P-Code function with a specific prototype, this is the trickiest part of the integration. Samples are available which pass in int, structures, references, Variants, bools and byte arrays. You will have to be very aware if arguments are being passed in ByVal, or the default ByRef (pointers).

Also pay attention to the function return types. If no argument/return type is defined, it defaults to a COM Variant. VB functions receive variant return values by pushing an extra empty one onto the stack before calling the function. Simple numeric return values are passed back in EAX as normal.

When interacting with callbacks make sure the callbacks are defined as __stdcall. All of the standard VB6 <–> C development knowledge applies. You can cut your teeth on these rules by working with standard C dlls and debugging in Visual Studio from the dll side while launching a VB6 exe host.

When in doubt you can create simple tests to debug just the function prototypes. For the complex prototype decryptor sample given above, I had the VB6 sub main() code call the rc4 function with expected parameters to test it in its natural environment. I could then debug the VB6 executable to watch the exact stack parameters passed to develop more insight into how to replicate it manually from my C loader.

This can be done with a native debugger by setting a breakpoint @6610664E on the ImpAdCallFPR4 handler in the VB runtime. Here you could examine the stack before entry into the target P-Code function. VBDec’s P-Code debugger is also convenient for this task.

When debugging it is best to have the reference copy of the VB runtime in the same directory as the target executable so that all of your offsets line up with your runtime disassembly with debug symbols. If you use IDA as your debugger, start with the disassembly of the VB runtime and set the target executable in the debugger options. Asm focused debuggers such as Olly or x64dbg are highly recommended over Visual Studio which is primarily based around source code debugging.

Conclusion:

When working on malware analysis it is a common task to have to interoperate with various types of custom decoding routines. There are multiple approaches to this. One can sit down and reverse engineer the entire routine and make sure your code is 100% compatible, or you can try to explore rip based techniques.

Ripping decoders is a fairly common task in my personal playbook. While researching the internals of the VB runtime it was a natural inquiry for me to see if the same concept could be applied to P-Code functions.

With some experimentation, and a suitable generator, this technique has proven stable and relatively easy to implement. These experiments have also deepened my insights into how the various structures are used by the runtime and my appreciation for how tightly VB6 can integrate with C code.

Hopefully this information will give you a new arrow to add to your quiver, or at least have been an interesting ride.

[1] Emit based rip

[2] Using an exe as a dll

[3] Running byte blobs in scdbg

[4] Malware IPC decoder service

[5] Code samples

[6] VB6 runtime with symbols

[7] VB6 internals video

[8] VBDec P-Code Debugger